FLORIDA

OF THE BRITISH

BRITISH COLONIALISM IN FLORIDA 1763-1783

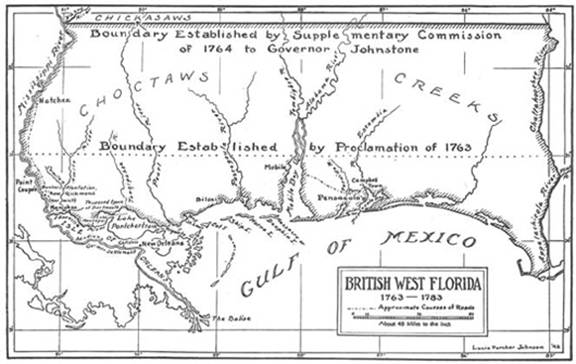

The British immediately divided Florida

into two distinct colonies with the Apalachicola

River as the boundary.

St. Augustine remained the capital of

East Florida, while Pensacola became the

capital of West

Florida. With poor road transportation and an enormous

voyage around the Florida Keys, the new

arrangement of two separate colonies allowed more effective administration than

the Spanish system.

The two Floridas

were Royal colonies governed by an appointed governor with a lieutenant

governor and a chief justice as primary staff members. The Crown also selected

a council to serve as the colony's upper house while British leaders promised

that an elected lower house would be chosen once the colonies developed a

population.

Both

colonies started as marginal endeavors, and like the previous Spanish

governors, Florida's

officials were obliged to save money from the contingency fund to keep public

services operating. The English, however, had one major advantage over the

Spanish: the ability to recruit permanent settlers, particularly families to

the New World. The British Parliament

cooperated by setting a goal of channeling migration away from the Indian lands

west of the Appalachians to newly acquired Florida. The Proclamation of 1763 outlawed settlement west of the Appalachians

while promoting Florida

as a new area of British colonization..

Unlike

agrarian Spain, England had strong desire to develop Florida trade. The London Board of Trade advertised 20,000 acre lots to any

group willing to enter Florida.

The land, however, had to be settled within ten years with one resident per 100

acres. While the Privy Council in London

granted land titles, pioneer families could gain land grants at the two

colonial capitals. Former British soldiers were eligible for special grants.

Each pioneer settler was given 100 acres of land and 50 acres per family

member. To recruit Southerners, slavery was allowed.

The wars

with France

had nearly bankrupted the government. The British Governors had to keep its

staff at a minimum: a secretary, an attorney general, a surveyor, a registrar

of titles, a trade agency, an Anglican clergyman, and two school teachers made

up the payroll. Careful use of the contingency fund might allow for the

additional recruitment of a coroner, a jailer, a clerk of court, and Indian

agents. Any new requests took six months to gain approval from London.

Each Florida was given a

single regiment of professional soldiers, good protection for the town folk,

but these men were also hired to guard the massive frontier from Indian attacks

and the coast from pirate invasions. The Governor had to summon the entire male

population into a state militia to

assure security. Since most settlers came from England,

Florida, like Virginia, made the Church of England

(Anglican) the official state religion.

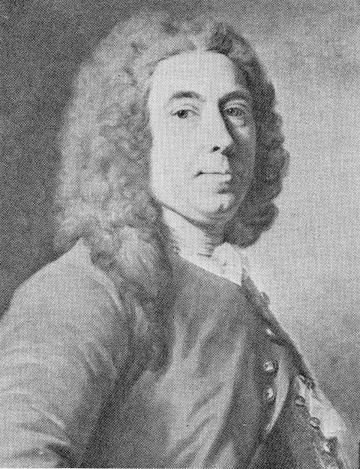

JAMES GRANT OF BRITISH EAST FLORIDA

No one did more to increase Florida's

population than JAMES

GRANT, the Governor of British East Florida.

During his administration, the Indians signed the Treaty of Fort

Picolata

which set boundaries between the two peoples. Philadelphia

botanists John and William Bartram

visited East Florida and reported the Timucuan villages were peaceful and prosperous under

Grant's rule.

Grant's

ability to recruit was reflected on the growth of the two colonies. East

Florida granted 2,856,000 acres to West Florida's

meager 380,000 acres. Those who entered East Florida

were predominately Europeans or Southern planters who regarded the region an

extensive of the Atlantic coastal plain. West Florida had to rely on pioneer

settlers from sparsely populated Alabama and

western Georgia.

It was

hoped that individual families who enter the region without the dependence of

grants from London.

Of 114 grants issued in 1776, only 16 families actually settled in Florida. More came to Florida by flatboat,

settled a riverside homestead, and never reported to the British authorities.

James Grant Developed The Port of Saint AUgustine

COLONIAL ATTEMPTS IN EAST FLORIDA

Grant recognized that rapid growth needed more than small homesteaders;

East Florida needed some major farming

developments. Grant himself built an estate outside St. Augustine, called

"The Villa", and promoted the cultivation of cotton and indigo.

One of his

first recruits was DENYS ROLLE, a Londoner inspired

by James Oglethorpe's success in Georgia bringing debtors into that

colony. Rolle brought in a collection of poor, unemployed, and petty criminal

settlers to a large plantation on the St. John's River.

Rollestown was an agricultural flop. Unlike

Oglethorpe's hand-picked farming colonists, Rolle

discovered his urban workers could not adjust to the hard labor and

inhospitable conditions of an isolated village miles

in a harsh tropical wilderness.

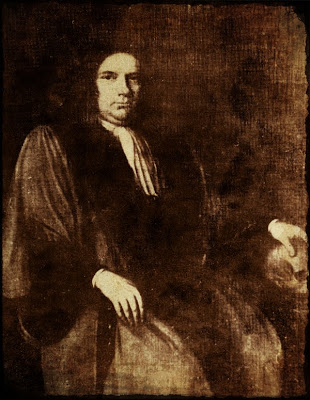

A more

original program of colonization was developed by Grant's friend and world

traveler DR. ANDREW TURNBULL. Turnbull

suggested that Florida would be an ideal spot for impoverished Greek, Italian,

and Minorcan peasants Turnbull had seen in his

Mediterranean travels. Certainly the climate of Florida would be more suitable to them than Rolle's Englishmen.

With this

incredulous dream and a land grant of 60,000 acres, Turnbull sailed to the

southern coast of Turkey

where Greek farmers, once the envoys of ancient Greek civilization, lived under

Turkish rule. He convinced many Greeks that Florida offered religious freedom and

greater success in sugar production.

On the

return voyage, Turnbull recruited many Italians and Minorcans,

and arrived in St. Augustine

with ships filled with 900 settlers. Governor Grant had hardly anticipated so

many new arrivals and realized Turnbull's "New Smyrna Colony", located down the

deserted Atlantic coast did not have enough food and shelter.

The

Turnbull colony was in trouble from the start. The English population

considered the Catholic Minorcans and Italians to be

potential allies of the Spanish in Cuba. Even more unfortunate, the

three cultural groups began to fight among themselves. Used to a mountainous

climate, the Greeks and Italians suffered in the hot Florida humidity. None of them had grown sugar nor was Turnbull

had effective businessman. He treated his indentured population like slaves.

The Minorcans fled to St. Augustine and others demanded to return

to their homeland. Dr. Turnbull's dream had collapsed.

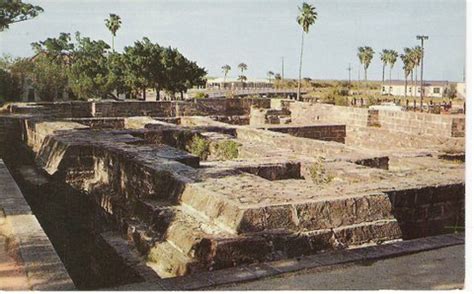

Remains of the Turnbull Colony at New Smyrna

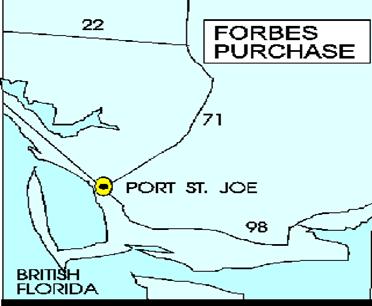

JOHN FORBES OF BRITISH WEST FLORIDA

While West Florida

lacked large scale migration, but it did have the FORBES PURCHASE.

In 1776 three American Loyalists, Willliam Panton, Thomas Forbes, and John Leslie, fled into British

Florida and started a trading company, Panton, Leslie and Company. Brother John Forbes was

chosen to be the business manager. When England

left Florida

in 1783, Panton and Leslie remained as agents for the

Indians in behalf of the Spanish administration. In exchange of cash payments

of debts, hundreds of Creek Indians living in West Florida gave the Panton Company over a million acres of land along the ApalachicolaRiver.

West

Florida was larger than East Florida and extended to Lake Pontchartrain,

Louisiana, but its leaders like George Johnstone had

serious problems with the increasing migration of Indians into the region.

Farmers and lumbermen would endanger the profitable fur trade with the Indians.

The

Spanish honored these land exchanges, but when the United

States finally gained Florida

in 1821, the U.S.

Congress denounced the Forbes Purchase. John Forbes recruited some American

investors and contested his land rights in the American courts. It was not

until 1835 that the courts yielded the land to Forbes and the American-based Apalachicola Land Company.

Unfortunately, most of the property was marshland unfit for sale.

The Forbes Purchase was Florida's Largest Land Grant

TOWN LIFE IN BRITISH FLORIDA

style='mso-bidi-font-weight:normal'>Florida

's few towns had larger populations than

the years of Spanish rule, but there was little change in the two decades when England operated the two Floridas. St. Augustine remained a

village of narrow streets lined with squat coquina houses and walled courtyards. The English residents,

at first ignorant of Spanish architecture, remodeled the houses until they

discovered the Spanish design kept out the winter wind and the summer

mosquitoes. They quickly adopted Spanish customs and a tropical lifestyle.

British

town life may have lacked some of the urban zest of a Spanish military

garrison, but it had families and some thirty trading ships per year. Tropical

goods and lumber were sent to South Carolina;

indigo dye and naval products to New

York. The work force was still quite limited, but

there was general optimism that British East Florida

would soon develop ties to the Enghlish colonies to

the North. The British also brought in a larger African-American slave populace

for the plantations.

Pensacola

and West Florida, with its sandy, coastal soils, and heavy forests, lagged

behind in development. The region produced no staple, money crops except lumber

and furs. The pioneer homesteaders who entered the area survived on crops of

corn, beans, cotton, tobacco, and rice. There were only a few plantations since

the fertile Tallahassee Hills were considered less secure from the Indian attack

for the frontier farmer.

BRITISH FLORIDA in the AMERICAN REVOLUTION

The outbreak of the American Revolution had a devastating

impact on British East and West Florida, for

its newly arrived population and its dependence upon English trade, assured

that Floridians would be loyal to the motherland. As the war broke out, the

confused and angry St. Augustine

residents burned effigies of revolutionary leaders Sam Adams and John Hancock. Loyalists easily outnumbered those who supported colonial protests over British trade policies.

Floridians

hoped the conflict would never reach Florida's shores, but England had decided to utilize Florida as a staging area for British troops

assigned to the South. Florida's warm climate

would accustom British forces to the American heat and Florida could develop supplies for the

British military. The huge fort at St.

Augustine was even turned into a prison camp.

The harsh

and conservative Loyalist Patrick Tonyn had replaced the retiring Grant as Governor of

East Florida and his heavy tactics upset

non-English immigrants. Tonyn did muster colonists

into the East Florida Rangers, a

militia that successfully halted American raids over the St. Mary's River.

In British

West Florida, there was general disorder.

Indians fled into Pensacola

and GovernorGeorge Johnstone

was recalled for disrupting military activities. In 1781 a Spanish fleet under

Bernardo de Galvez sailed into Pensacola Harbor

from New Orleans

and bombarded the city. His mission was limited, but it terrified the small

community. Spain used this attack to demand the return to Spain of Florida at the end of the American Revolution.

The

British occupation of Savannah and Charleston placated much of the fear in British Florida until the stunning defeat of Cornwallis at Yorktown. The Revolution was over. The revolting colonies

had won even if there was only a truce. Loyalists poured into St. Augustine from across the south. They

would have made the city an economic boom town, but nearly all of them were

headed to the Bahamas,

Bermuda, or England.

It was not

until the Treaty of Paris

in 1783, that Floridians discovered their fate. To the shock of most Floridians, Florida was

not going to be part of the United

States. Southerners were even more shocked

that their delegate in Paris had missed the

ruling on Florida.

With that news, most of the English in St. Augustine

became to pack for England

or the British Caribbean, leaving the Catholic

Minorcans in a deserted town.