FLORIDA OF THE CONQUISTADOR

MONARCHY AND MERCANTILISM IN FLORIDA

Unknown to the Indians of Florida, their destiny was being

determined by political and economic forces taking place across the Atlantic

Ocean in Europe. At the end of the fifteenth

century, thousands of daring adventurers would be crossing the ocean to conquer

within a few centuries what had taken the Indians thousands to years to

inhabit.

This "Age of Exploration" was fostered by the development

of maritime technology and the belief in an economic philosophy called

mercantilism which decreed that a nation that was not self-sufficient will

be dominated by its neighbors. The discovery in 1492 for another hemisphere by

Christopher Columbus shifted the need to travel west to the Americas as the focus. European lands located on the Atlantic like Spain, France, and England could now avoid middlemen like the Arabs and Italians to reach the spice and gold of the Far East.

GOLD, GLORY, AND GOD AS GOALS

The conquistadors of Spain who ventured into the lands

of the Indians were motivated by many forces. The discovery of gold in Mexico and Peru convinced thousands of

impoverished Spanish peasants to join the military. Men fropm wealthy families also joined the cause of exploring the New World. Under the rules of

primogeniture, younger sons of the nobility would not inherit much of the

family estate, but leading a successful colonial mission could give you the

funds to build a castle.

Others sought glory and fame, now that the wars with the Moors were over.

Only in the New World was there the

opportunity for quick advancement in the Spanish military and diplomatic

careers.

Finally, there were those who came for spiritual reasons. They were more

than just the priests and church leaders. Catholic Spain had a strong

missionary zeal, for they had engaged the Muslim infidels for four centuries. Colonial budgets were designed to spend 10% of its income on serving the Indians, although clever leaders found ways to construct missions next to mines. In Florida, there would be no mineral wealth.

The eternal blessing of God would be earned by converting the Americas into Catholic lands.

PONCE de LEON - MAN OF MANY MYTHS

JUAN PONCE DE LEON who is acknowledged as the

discoverer of Florida. MYTH: Ponce de Leon discovered Florida. REALITY: John Cabot probably reached Florida's East Coast on his 1497 voyage based upon his son Sebastian's descriptions. Since there existed two ancient maps (the 1502 Cantino Planisphere and the 1511 Peter Martyr) showing the southern half of Florida which predate Ponce de Leon's trip to Florida. Thus, Ponce did not discover Florida but verified it was part of North America.

The grandson of a famous war hero, Ponce

de Leon was trained to be a soldier and public servant. This indicates he was not a man of wealth despite the notability of his family background. When the Moors were defeated, the opportunity for financial advancement shifted to the exploration of the New World to the sea. His relatives perhaps got the landlumber on Columbus' huge second voyage. He probably returned to Spain but soon went to Hispaniola with newly appointed governor Nicolas de Ovendo. He defeated the Indians and was given land for a plantation on Hispaniola (Dominican

Republic).

His duty to serve Spain would end his retirement. Columbus had been made adelantado (military governor) for life, but upon his

death, Spanish authorities refused to grant such privileges to his son Diego.

The Crown selected Ponce de Leon to colonize Puerto Rico, a task he accomplished with just a few

troops and one greyhound who scared the natives.

Ponce de Leon - The First Attempt to Colonize Florida

Meanwhile, Diego Columbus had taken his claim

to the courts in Madrid

and won his rights. Ponce

de Leon was removed from office and felt his good name had been damaged. He was married with three kids and the owner of a succesful farm, but felt he had been dishonored by his removal of office. MYTH: Ponce de Leon found Florida while looking for the Fountain of Youth. REALITY: Ponce was in good health. Not

wishing to serve Diego, Ponce de Leon obtained

title to explore the Upper Bahamas and areas

to the North. Ponce de Leon did not see any Florida maps prior to 1513, but no one knew from Cuban slavers and from notes about the Florida Straits that Florida was either a huge island or part of North America. If it was the latter, Diego could not claim it since his father never reached the mainland.

In March of 1513, Ponce

de Leon sailed into the Bahamas

headed toward Florida,

then considered by slave hunters and fishermen to be a large island. Now Ponce's boss the King of Spain believed in the Fountain so on his return voyage Ponce sent TWO men to Bimini, an island where a great spring was said to be located. Ponce was in reality seeking a spiritual rebirth and a return to his status as a great leader with new honors, not a

physical rebirth with some magic water. Ponce de Leon did not even mention the Foutain of Youth in any of his fairly detaled sea reports. It would be later Spanish historians that noted Ponce de Leon's quest for the fantastic spring.

On Easter Sunday, March 27, 1513, his crew

sighted land, probably Abaco

Island. Six days later he

reached the Florida coast and sailing

northward to land from Melbourne to St. Augustine.

He named the place "Pescua Florida", "the place of

flowers," perhaps in honor of Easter Sunday. On the return voyage he

encountered Indians near Jupiter Inlet and charted the important features of

the Florida

East Coast. He rounded the Dry Tortugas to explore the Gulf of Mexico and

entered Charlotte

Harbor.

He realized that Florida was more than a large island. He saw

the chief Calusa village near Mound Key and

discovered this tribe was unfriendly. He selected Estero Island

to repair his vessel and escaped as bands of Calusa

descended on the intruders.

THE SECOND VOYAGE OF PONCE DE LEON

It would be eight years before Ponce de Leon could get funding for a second trip to Florida. Hernando Cortez

had conquered the Aztecs and Spanish interests shifted to Central

America. Ponce

de Leon was able by 1521 to get only small financing.

In the winter of 1521, Ponce

de Leon headed for Calusa

Territory with a 500 man force,

including Florida's

first priests, farmers, and artisans. They landed on the Gulf beaches between Charlotte Harbor

and Estero Bay. His goal was to establish a

permanent colony in South Florida.

The choice of location proved weak. Requiring

food and fresh water, Ponce

de Leon led some troops into the dense coastal forest for a spring. Suddenly,

the conquistadors were ambushed from all sides by Calusa

warriors. The European weapons were rendered ineffective by the close combat. Ponce de Leon was pierced

in the thigh by a reed arrow.

The soldiers carried their wounded adelantado to the ships. The colonists agreed to return to Cuba

and evacuate the project. Ponce de Leon promised to return, but his health

deteriorated and he never saw his discovery again.

LESSER GLORY SEEKERS

Florida was visited by other explorers, but

the lack of visible rewards discouraged attempts at settlement. In 1516 Diego Miruelo mapped Pensacola

Bay. Alonso Alvarez de

Pineda, a survivor of an ill-fated landing in Calusa

country in 1517, traveled the Florida shore to the Mississippi River, verifying

Ponce de Leon's claim Florida was not an island.

In 1520, another merchant in search of Indian

slaves for Caribbean mines, Vasquez de Ayollon,

mapped the Carolina

coast. Spain claimed the

entire region as part of Florida.

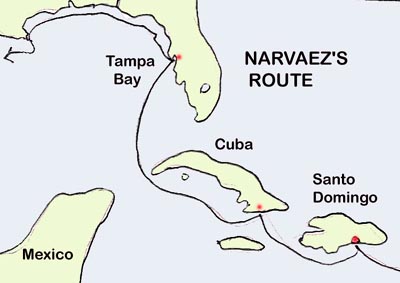

PANFILO de NARVAEZ

The wealth of Mexico

inspired many explorers, but none more seriously than PANFILO DE NARVAEZ. Narvaez was a

veteran Caribbean soldier who had been hired

by Spanish authorities in 1520 to overthrow Hernan

Cortes' tyrannical rule. Cortes captured Narvaez and imprisoned his would-be

conqueror for three years. Upon his release, the one-eyed soldier sailed to Madrid to obtain a grant to colonize the Gulf Coast

from northern Mexico to Florida,

It was at the Spanish court where Narvaez met

a devout nobleman named Cabeza de Vaca,

who wished to duplicate the exploits of his grandfather who conquered the Canary Islands. The red-haired conquistador hired de Vaca as a partner and together in 1527, landed north of the

mouth of Tampa Bay with an armada of five ships and 400

soldiers.

At a nearby Indian village, the explorers

discovered some crude gold ornaments. Infatuated with the idea of uncovering

another Mexico,

Narvaez seized as hostage the regional Indian leader Ucita.

When the chief wouldn't reveal the source of the treasure, undoubtedly the

result of long range trade, Narvaez chopped off the Indian's nose. Ucita made up a story about the great wealth of the Apalachee.

The Ruthless Narvaez Had Five Ships and Over 400 Soldiers

Against de Vaca's

judgment, Narvaez ordered his ships back to Cuba, while the rest of his forces

headed northward in search of gold. The Narvaez expedition would ruin

Spanish-Indian relations for decades. They left behind a legacy of violence and

trickery. In the Tallahassee Hills, Narvaez would find only farming villages.

Narvaez's fleet returned to Tampa Bay, but found no sign of the expedition which was still

marching along Apalachee territory. They ended their

search and returned to Cuba,

where Narvaez's wife hired a group of sailors to find her husband. It was this

rescue party that discovered what they believed was a message on a reed on a

deserted beach. A young Sevillian Juan Ortiz went to

retrieve the message and was captured by the Indian trap.

Ortiz claimed he was brought to Chief Ucita to be executed, but rescued by the daughter's chief

in a scene which preceded the famous Pocahontas story. In fact, many believe

John Smith "stole" the Ortiz story to tell of his great dealings with

the Indians in Virginia,

since the Pocahontas legend was written four years after the Indian woman's

death. While Ortiz was fighting to survive, Narvaez was wandering Panhandle Florida in search of

treasure. Narvaez finally returned to the Gulf at St. Marks and, assuming

Mexico to only be a few days journey to the west, constructed five long canoes.

They sailed as far as the Texas

coast where a storm capsized the boats.

Narvaez drowned. Cabeza

de Vaca and four other survivors reached an Indian

village where they resided for two years. In was not until July of 1536 and six

thousand miles that de Vaca reached Mexico

City to report the fate of Narvaez' 280 man mission into Florida.

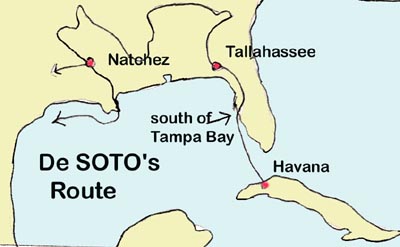

DeSoto's Greed Sent Him on a Wild Trip Across The South

HERNANDO de SOTO

Cabeza de Vaca became a living

legend among Spanish administrators in the Caribbean and no one listened more

intently than HERNANDO DE SOTO, a wealthy captain from Pizarro's Inca conquest.

He petitioned Spain to

become Governor of Cuba and adelantado of La Florida.

In the spring of 1539, he sailed for Tampa Bay,

leaving his wife as Governor of Cuba.

With seven vessels, six hundred soldiers, three Jesuit friars, and several

dozen civilians, he fully intended to start a settlement. On May 25, he landed

near Tampa Bay,

probably in the mouth of the Manatee

River. He sent out his

cavalry to contact the neighboring Indian tribes.

At

a village called Hirrihigua, the Spanish met Ucita, the noseless victim of

earlier Spanish cruelty. The cacique led DeSoto to a

nearby village where he found Juan Ortiz, alive after twelve years with the

Indians. DeSoto recruited Ortiz as an interpreter and

guide.

At

a village called Hirrihigua, the Spanish met Ucita, the noseless victim of

earlier Spanish cruelty. The cacique led DeSoto to a

nearby village where he found Juan Ortiz, alive after twelve years with the

Indians. DeSoto recruited Ortiz as an interpreter and

guide.

WHERE DID DeSOTO

GO?

Historians have debated the route of DeSoto along Florida's Gulf Coast

for years. While many state DeSoto landed in Manatee County,

where the National DeSoto Memorial is located, others

like Donald E. Sheppard, believe DeSoto landed in Charlotte Harbor.

Like Narvaez before him, DeSoto

was so attracted to the tales of rich Indian villages to the North,

he deserted all plans to establish a real colony. He sent the fleet back to Cuba and left only a base camp on the Manatee River. With an army of Indian prisoners

as guides and a herd of hogs for food, DeSoto's army

marched inland from the marshy coastline. Still, it was summer and the mosquitos and heat penetrated the armored woolen uniforms.

At Ocali, they found a Timucuan

village notable only for its agriculture.

The Timucuan

convinced DeSoto to visit the Apalachee

in the Tallhassee Hills. By capturing local leaders,

the Spanish reached the Apalachee where corn and

shelter were common. By now, the greed for wealth was the major motive for the

conquistador.

In the spring of 1540, DeSoto's

forces with their herd of hogs headed northwestward into Georgia, never to enter Florida again. For the next three years, DeSoto would explore the frontiers of Georgia, South Carolina,

Tennessee, Alabama,

Arkansas, and Mississippi. At Guachoya

(Ferriday) in Arkansas,

the great soldier died of the fever. Juan Ortiz would later drown. Only a few

of DeSoto's troops survived the long journey.

FATHER LUIS CANCER

Not all Florida missions were economic in scope. The

Government of Mexico

financed a mission by FATHER LUIS CANCER, a Dominican priest. In 1549, Father

Cancer, three other missionaries, and a Christianized Indian maiden named

Magdalene arrived on the beaches outside Tampa Bay.

Considering the Indian's previous experiences with white men in this area, it

was a poor choice of location.

Cancer left two men and Magdalene on the

beach while he searched for safe harbor inside the bay. When he returned he

spotted only the Indian girl on the beach. Despite warnings by the crew, Father

Cancer elected to go ashore. He was quickly surrounded by Indians who clubbed

him to death. The survivors of the party returned to Mexico

to quell any future missionary proposals for Florida.

TRISTAN de LUNA

In 1559 Don Luis Velasco, Viceroy of Mexico, decided that a Florida settlement on the Gulf was essential

in helping shipwrecked sailors and discouraging French trading visits. He chose

a wealthy, religious, but temperamental soldier named TRISTAN DE

LUNA to establish a colony.

With

an enormous force of thirteen ships and 1500 soldiers, de Luna landed at Pensacola Bay. Velasco's choice of leader proved

unworthy. Leaving the ships in the Bay for two months while

he explored the region. He sent his aide Villafane

to the Atlantic Coast to erect a colony rather than

consolidating his efforts. A storm destroyed five of his ships.

With water-logged supplies, de Luna turned to

the nearby Nanipacna Indians along the Alabama River for food. The local Indians, remembering DeSoto stayed away. The colonizing effort was replaced with

a desperate need to stay alive. After a winter of near starvation, the settlers

tried to plant crops on the sandy coastal soil and gave up. The expedition was

canceled.

THE EMANUEL POINT SHIPWRECK

In 1992 a team from the Florida

Bureau of Archaeological Research found the remains of a Colonial Spanish ship

in Pensacola Bay. The ship may have been one of de

Luna's 1559 ships destroyed in a storm.

AFTERMATH

The disastrous results at Pensacola

disillusioned King Philip II of Spain.

He was one of the few men in Madrid who

understood that Spanish settlements in Florida

would discourage English or French activities against the Spanish gold

flotillas in the Gulf of Mexico.

Between 1513 and 1560, the Spanish had failed

to construct a single town in La Florida

despite numerous expenditures. Experienced soldiers like Narvaez and DeSoto had chosen treasure for settlement.

On September 23, 1561, the monarch

reluctantly announced that Spain

was no longer interested in promoting colonial expeditions into Florida. For all

practical considerations, the Spanish seemed willing to let Florida to fall into obscurity.