NEW WAVES OF CHANGE

THE NEW FLORIDA:

1876-1919

THE NEW BOURBON MAJORITY

The return to political power of the Bourbon Democrats did not mean the

overnight destruction of reforms of Reconstruction. Governor George F. Drew was an old-timer Whig, a native of New Hampshire, and a

lumber man with Northern contacts. Drew supported closer contact with Northern

investors and a new diverse economy.

Florida's

backwardness and the need to rebuild the state economy were major

considerations which even the agrarian interests could not overlook. The cotton

kingdom was declining as new cotton fields opened in Texas. The Bourbon Democrats were still

politically conservative, but they weren't ignorant of the realities of Gilded America.

Florida's

backwardness and the need to rebuild the state economy were major

considerations which even the agrarian interests could not overlook. The cotton

kingdom was declining as new cotton fields opened in Texas. The Bourbon Democrats were still

politically conservative, but they weren't ignorant of the realities of Gilded America.

They were

also the major party in Florida

as their Black Codes systematically eliminated most of the African-American

vote, essential to the survival of a statewide Republican Party. Only in Jacksonville and Pensacola

were blacks still in public office by 1880, thanks to Democratic

gerrymandering. The Bourbon plan for a new state constitution in 1885 to oust

the Reconstruction Constitution was the final legal nail on the coffin of

politics.

The Civil War had not ended the status of

the agrarian classes. Most rural African-Americans and poor whites found

sharecropping and tenant farming the only routes to survival in much of

Panhandle Florida.

Others choose to vote with their feet by leaving rural Florida. However, until most of the Deep

South, many Floridians headed southward rather than to the North due to the

development of peninsular Florida.

Florida was

the only Southern state in the South who gained black people in the migration

between states.

The Civil War had not ended the status of

the agrarian classes. Most rural African-Americans and poor whites found

sharecropping and tenant farming the only routes to survival in much of

Panhandle Florida.

Others choose to vote with their feet by leaving rural Florida. However, until most of the Deep

South, many Floridians headed southward rather than to the North due to the

development of peninsular Florida.

Florida was

the only Southern state in the South who gained black people in the migration

between states.

FLORIDA ON THE RIM OF THE SOLID SOUTH

Florida politics in the 1870's and 1880's remained

on the rim of the Solid South. sharing many of the serious problems facing the

South after Reconstruction, but other areas of Florida resembled the Western frontier boom,

complete with pioneer farmers, cattlemen, conflicts with the Indians, and

railroad tycoons. Racism was still a factor in Florida,

but did not dominate the dogma of Florida

politics as it did in other Southern areas.

Florida leaders

accepted the notion that Northern moneys were essential to develop South Florida and were reasonably hospitable to the needs

of Northern investors and visitors. The danger of Populist radicalism,

influential in some Southern states by 1885, was treated as another force of

change entering Florida.

The

Constitution of 1885 and the Black Codes had disfranchised minority opposition.

By participating and regulating the Northern investment into Florida,

most Bourbon Democrats felt a careful alliance with these newcomers would

establish "a new Florida",

a blend of Northern technology and old Southern ways. They thought they would

convinced Northerners of the merits of their goals. In any case, material

progress could bridge a lot of differences.

FEARS AND REACTIONS IN GILDED ERA FLORIDA

Rapid changes and a greatly restrictive political system were bound to

create a good many critics. The Constitution of 1885, which would last well

into the twentieth century, may have made Cabinet posts, Supreme Court judges,

and regulators elected officials for the first time, but it was not a document

for reform. The agrarian aristocracy soon allied with the new wealth of

railroad men, lumber men, and citrus growers.

A leading

spokesman for the small farmers against the railroads was Wilkinson Call, a

colorful Populist who got the State of Florida

to establish a Florida

Railroad Commission to stop unfair rate practices. Henry Flagler and Henry

Plant couldn't silence Call.

Less

easily understood by many urban Floridians was the intense development of

Nativism in Florida.

The continued growth of the Klu Klux Klan and other militant groups was due not

just to the demise of black political influence, but due to a fear of the waves

of change entering Florida.

Northerners were changing old institutions.

By the late

1890's this emotional nativism was also directed at the Roman Catholic Church

in Florida.

Under the demagoguery of Tom Watson and the Guardians of Liberty, many rural Floridians believed that

Catholics were loyal only to the Pope. By 1916, anti-Catholic sentiment helped

bolster an obscure Defuniak Springs minister Sydney Catts into the Florida

Governorship. Catts never enacted his most serious attempts to close down

monasteries and nunneries and a counterattack led by Father Michael Curley

changed public opinion in the large cities.

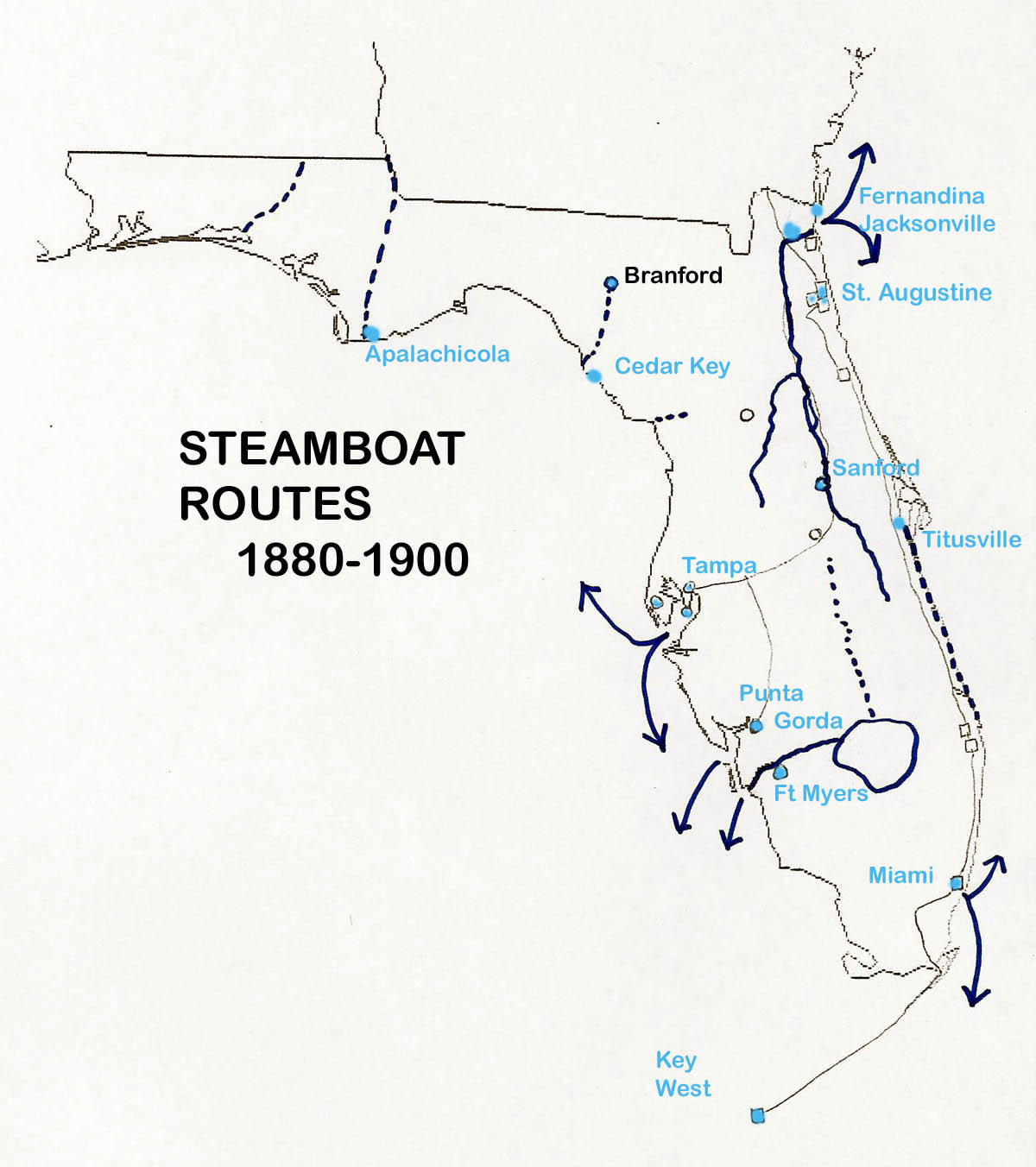

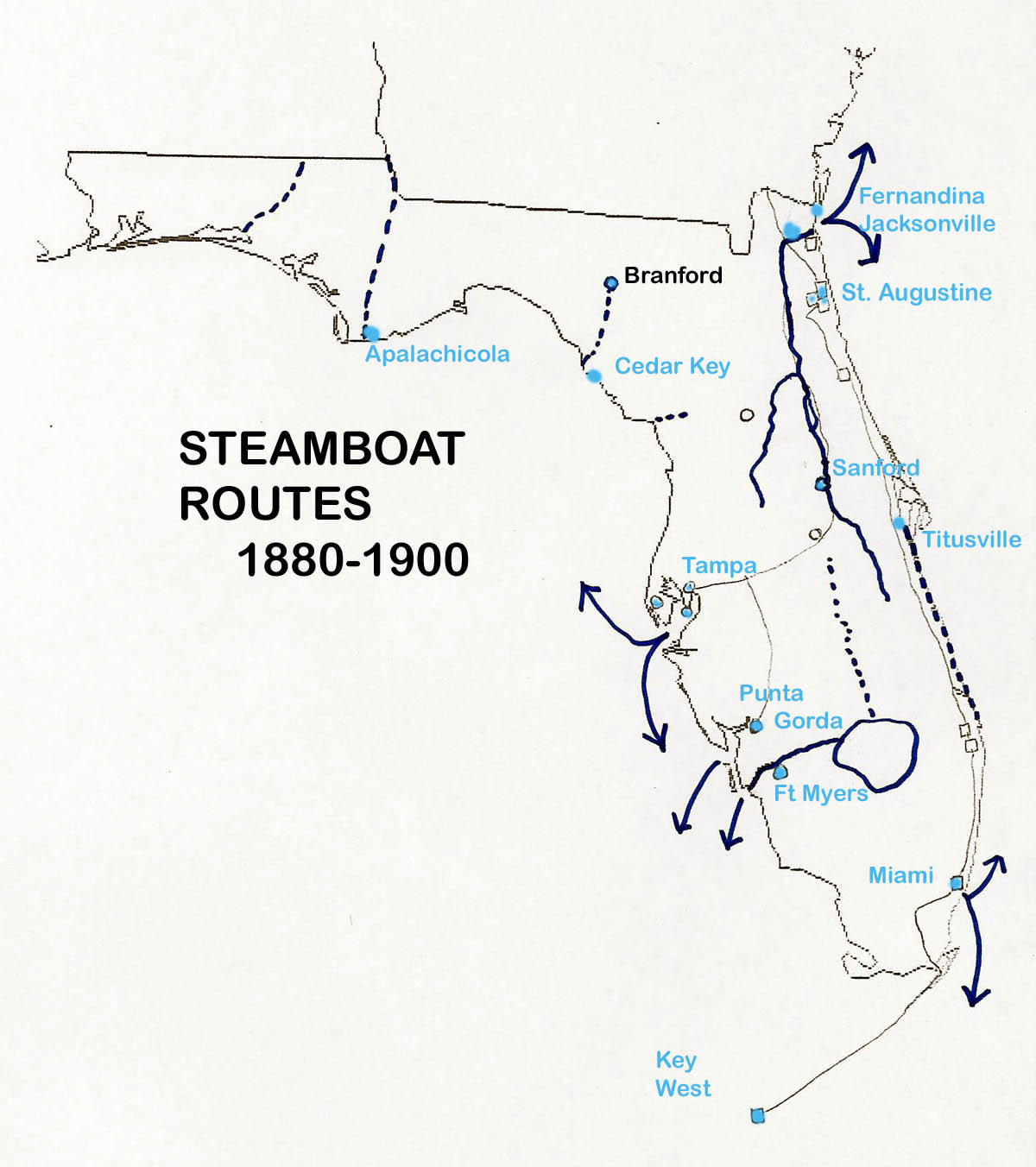

LAST DAYS OF THE STEAMBOATS

While the development of huge railroad lines in the 1890's would

forever end the glamour of riverboat transportation, the Gilded Era was a time

of wonderful steamboat transportation for visitors and Floridians alike. The Yulee rail line from Jacksonville to Cedar Key offered an eighteen

hour excursion where the engineer often stopped the train to check his game

traps along the rail bed.

For thirty

short years, steam boating down the St. Johns River and along the Atlantic Coast became the winter activity for

thousands of Northerners. These Gilded Age travelers started the first regular

tourist industry in Florida

and helped establish dozens of hotels and restaurants that catered to

vacationing tastes.

Steamboats were floating palaces, offering personal service. Fernandina

Beach was the major port for many coastal steamers, although Jacksonville was

the major departure point for the St. Johns River steamboat industry, which in

its peak offered one hundred boats.  Towns like Palatka shifted from

agriculture to tourism. Everyone seemed to be riding the steamboats. Robert E.

Lee and U. S. Grant took

farewell voyages down the St. Johns River.

Harriet Beecher Stowe waving on the front porch of her winter home in Mandarin

was a popular tourist sight. In 1888 Jacksonville

held the Subtropical Exposition,

Florida's

first World's Fair. President Grover Cleveland attended and then jumped on a

steamboat.

Towns like Palatka shifted from

agriculture to tourism. Everyone seemed to be riding the steamboats. Robert E.

Lee and U. S. Grant took

farewell voyages down the St. Johns River.

Harriet Beecher Stowe waving on the front porch of her winter home in Mandarin

was a popular tourist sight. In 1888 Jacksonville

held the Subtropical Exposition,

Florida's

first World's Fair. President Grover Cleveland attended and then jumped on a

steamboat.

Steamboats

on the Suwannee and Apalachicola were smaller

boats catering more to locals. They lacked the color of St.

Johns vessels like the City of Jacksonville, a $120,000 electric lit

floating palace. Races between rival boats were not just for spectator

entertainment but to convince customers of the merits of the boats. When the

Baya and John Sylvester crashed in a race, the state outlawed the racing

practice.

Steamboats

also took citrus to the North. In 1890, it was discovered that a 12 by 12 by 27

inch crate could safely carry citrus to Northern destinations. Few winter

visitors failed to send shipped fruit back from Florida's

first citrus empire, the St.

Johns Valley.

SPONGING AND WARRIORS OF THE SEA

Rapid railroad and coastal shipping also benefited Florida's long established fishing industry.

South Florida was dominated by Cuban and

Northern fishermen until the profitability of fishing convinced investors to

purchase boats.

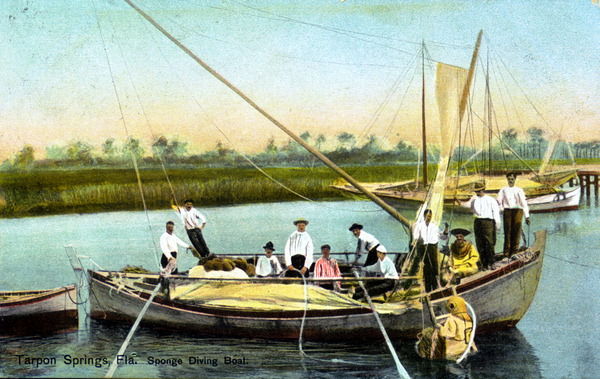

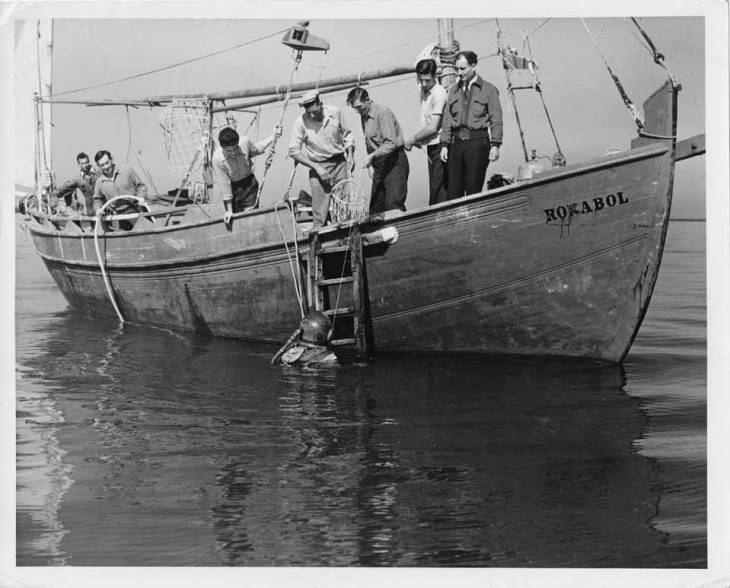

The Conchs, the natives of Key West, dominated not just fishing in the Florida

Keys, but also developed a successful sponging operation, using glass bottom

boats and sixty foot spears. This technique could only be utilized in calm

water and along the shallow keys.

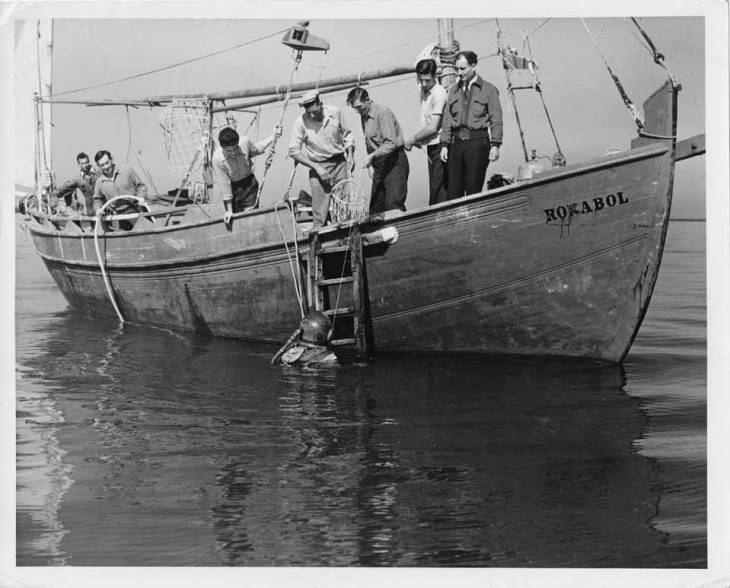

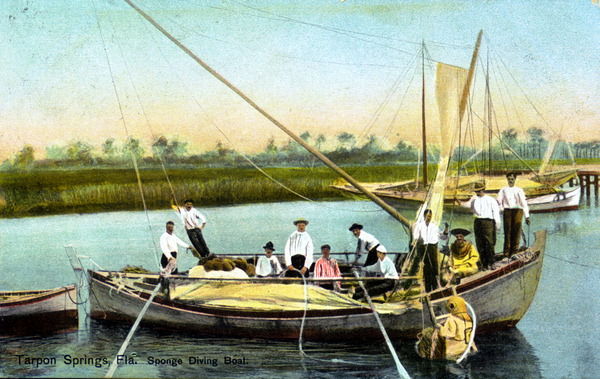

In the

1880's Tarpon Springs businessman John

K. Cheyney recruited a New York sponge

merchant named John Cocoris to start a sponge fleet in the bayous and springs

of North Pinellas County.

Cocoris brought in divers from the Aegean

Islands. These Greek

fishermen introduced diving tanks, which revolutionized the Florida sponging industry and delegated the

Conch's to secondary spongers.

Soon 200 sponge ships operated out of

Tarpon Springs and a vibrant community of Greek Orthodox settlers was added to

the waves of change in Florida.

Soon 200 sponge ships operated out of

Tarpon Springs and a vibrant community of Greek Orthodox settlers was added to

the waves of change in Florida.

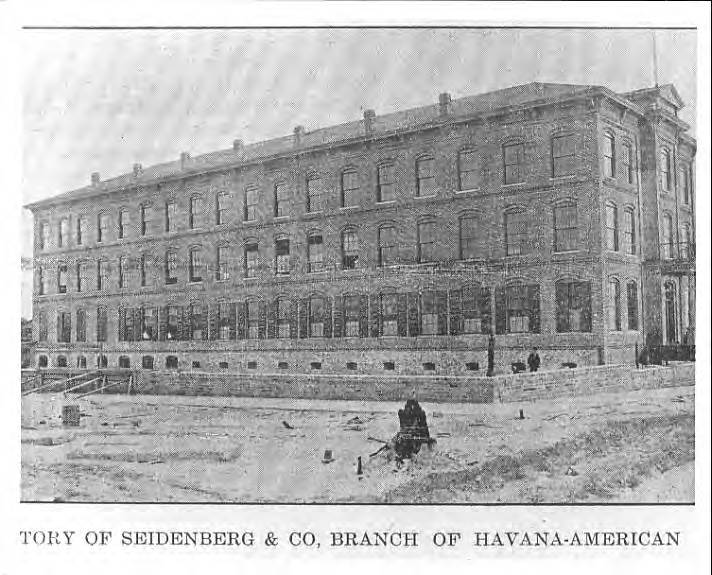

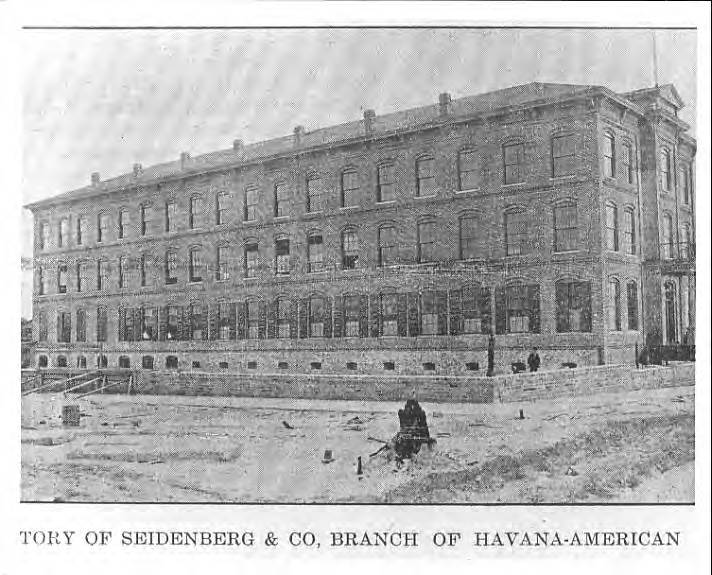

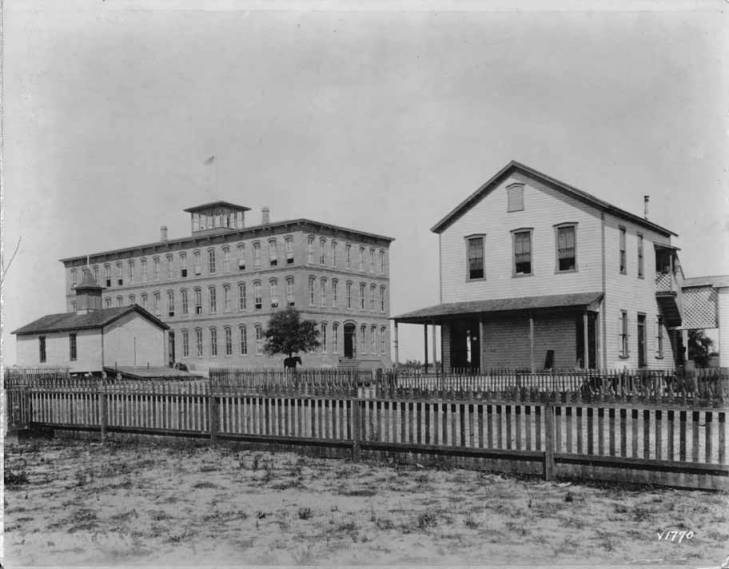

THE CIGAR INDUSTRY OF TAMPA

The Cuban Revolution of 1868 send many Havana

cigar manufacturers to Key West

to avoid the conflict and to develop American markets. Key West proved a costly location since most

advantages was with organized labor.

The

arrival of Henry Plant's railroad to Tampa

Bay would cause a major

change. Key West cigar maker Vicente Martinez

Ybor obtained forty acres of land just northeast of downtown Tampa in 1885. As he imported skilled Cuban

cigar makers, Spanish cigar manufacturers and German box makers flooded into Ybor City,

and later developments in West Tampa, Palmetto

Beach, and Port Tampa.

Photographs from Burgert Brothers Photo Collection, Hillsborough-Tampa Public Library Cooperative

Photographs from Burgert Brothers Photo Collection, Hillsborough-Tampa Public Library Cooperative

As Ybor City

boomed, the shocked Tampa

Anglo community decided to incorporate the Latin areas into the city's Third

Ward and assure the control of local politics. Still, Ybor

City changed Tampa into the South's first multiethnic

manufacturing port complete with labor organizations and ethnic clubs.

By 1900 60% of the workers were Cuban (about one-fourth Afro-Cuban), 23% Italian from the Agrigento province of Sicily, and 17% Spanish mainly from Galicia and Asturias. Each ethnic group formed their own clubs and organization. While Spanish and Italian families generally remained in Tampa, the nearness of Havana, just one day by ship, meant many of the single men returned to Cuba.

Most Tampa workers found the Cigar Makers International Union of America (CMIU) too dominated by German cigar making and philosophy, the CMIU continued to try to unite the Tampa cigarmakers with Northern cigarmakers. In bad ecoomic times and times of labor strife, the CMIU recruited Tampans, but the Latin traditions of a rigid status hierarchy of workers of various skills remained strong in Tampa. Tampa's cigarmakers did not fully accept the rules and proceedures from Northern unions. The decline of the local La Resistence union after the 1899 strike helped the CMIU by 1908.

While the fear of immigrants after WWI negatively effected the cigar industry, there were greater economic forces at work to cause the gradual decline of cigarmaking. The rise of cigarettes and cheap mechanized cigar making systems were part of a changing AMerican culture. Second and third generation Latin immigrants in Tampa were going into other occupations or leaving the region alltogether.

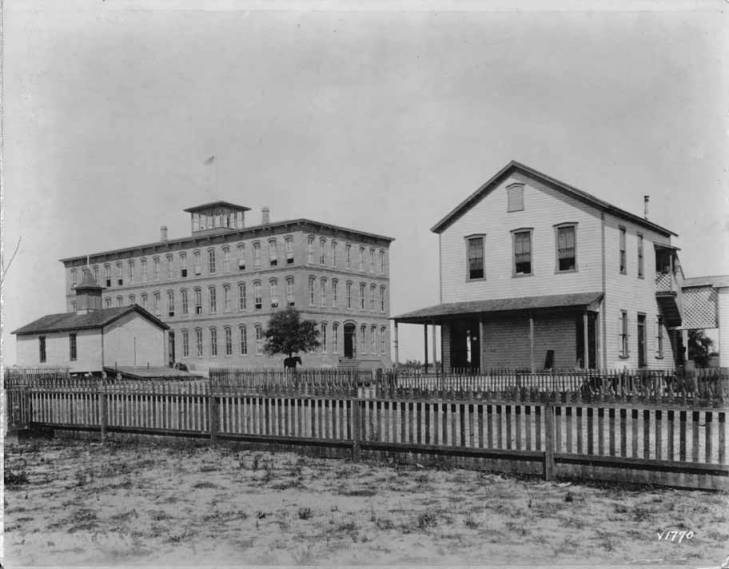

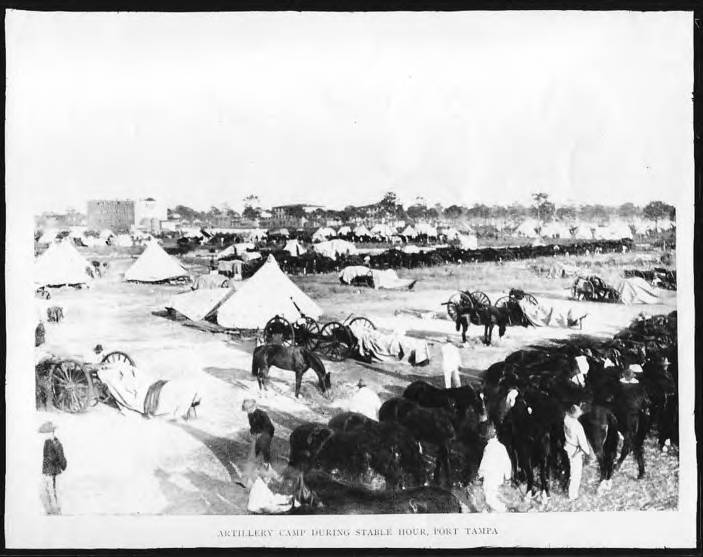

THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

Tampa was also the focus of an event that put Florida on the map around the world.

Floridians had been spared the heart-ship of war for forty years, when, almost

overnight, they found a war thrust upon them due to the state's closeness to

Spanish Cuba and the large

Latin population of Tampa.

The desire

of the independence of Cuba

from Spain was not just the

dream of the thousands of Cuban immigrants in New York City

and Florida,

but also of American businessmen who had millions invested in the island.

Floridians not only supported the Cuban revolutionaries, but many Floridians

had participated in gun-running and fund raising for years.

Next to New York City, Tampa's Ybor City

and West Tampa were the centers of Cuban

revolutionary organization. Jose Marti, the George Washington of Cuba, came to Florida many times to

unify the diverse Cuban groups. He was also poisoned by Spanish agents in Ybor City.

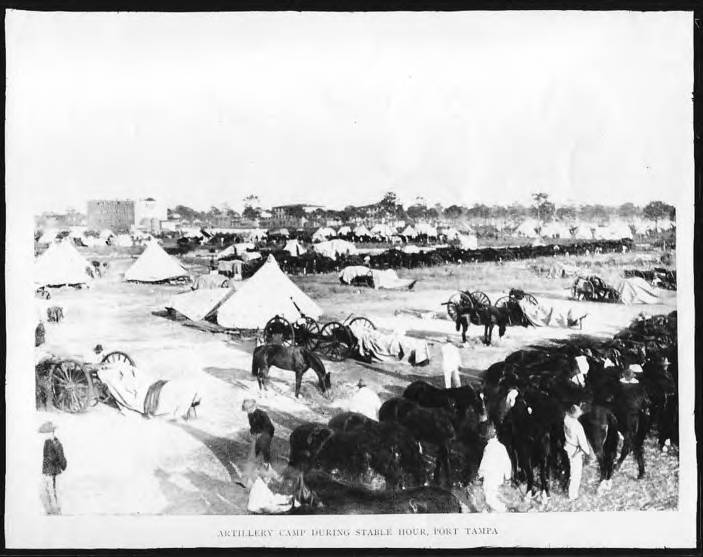

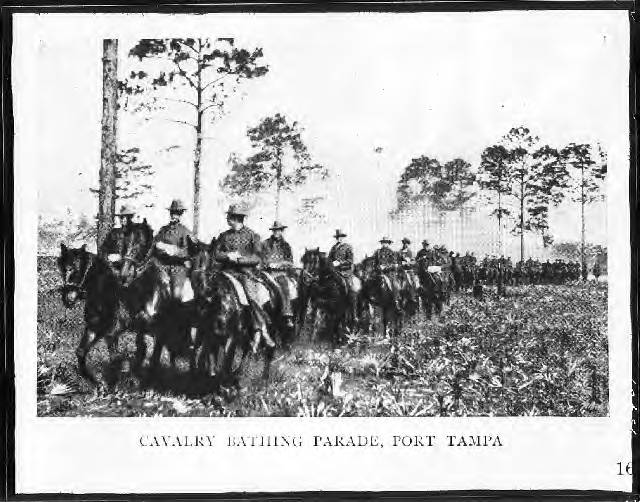

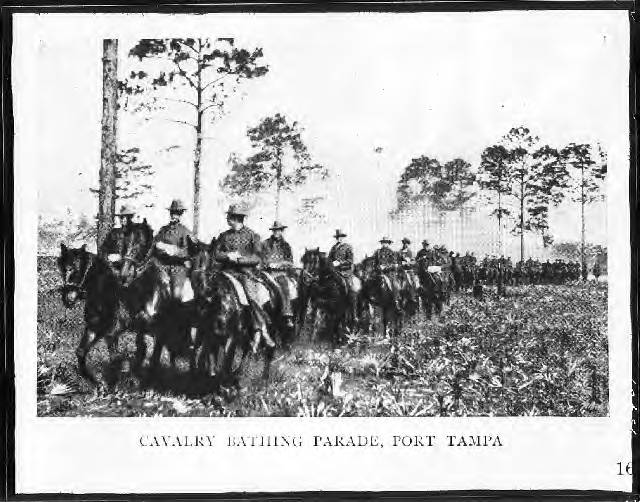

When war

finally came, after the mysterious sinking of the battleship Maine,

Tampa was selected as the demarcation port for

the invasion of Cuba and Puerto Rico. Some 23,000 volunteers, an international

press corps, 20,000 observers, and Teddy

Roosevelt and his Rough Riders made Tampa an exciting and confusing global

village.

Photographs from Burget Brothers Collection, HCPLC

Photographs from Burget Brothers Collection, HCPLC

The United States

was not prepared for a war. Thousands of freight cars piled up for three

hundred miles. The Tampa Bay Hotel was packed for the first time. There was a

fear of a race riot, for this was the first time Northern, black, and Southern

white units were organized into one military force.

Clara Barton feared Americans would die of yellow fever. Plant's Port Tampa docks could not dock

the 100 ships so horses and supplies couldn't even be loaded into the last

vessels. Fort Desoto,

built at the entrance to Tampa

Bay to stop the Spanish,

was a total waste of construction since it was based on a ship channel map

produced by Colonel Robert E. Lee in the 1850's.

When it

became obvious that all the troops could not fit onto the crude armada, more

soldiers were hurt piling into the ships than landing in Cuba. Finally, General William Shafter agreed to let

the invasion force set sail. The entire world had discovered Tampa.

FLORIDA

IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA

The Spanish-American War had started a construction boom that would

continue into the 1920's. Many of the soldiers returned to Florida

after seeing how inexpensive land was compared to the Great

Plains and North.

In 1900,

the last state convention of the Democratic Party of Florida

met in Jacksonville.

From then on, Floridians would select their candidates in state primaries.

Rather appropriately, the candidate of the conservative Bourbons D. H. Mayes

lost to reformer William Sherman Jennings.

Jennings proposed to expand the role of state

government with programs to help the poor and develop more schools. He even

talked about draining the Everglades for land

reform. Despite these measures, Jennings

was still part of the Bourbon aristocracy that kept minorities and outsiders

under wraps with Jim Crow laws and careful regulations.

Jennings proposed to expand the role of state

government with programs to help the poor and develop more schools. He even

talked about draining the Everglades for land

reform. Despite these measures, Jennings

was still part of the Bourbon aristocracy that kept minorities and outsiders

under wraps with Jim Crow laws and careful regulations.

Jennings' successor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward had

been a gun smuggler in the Spanish-American War and a ruthless opportunists.

Broward was also a firebrand against some of the old power structure and backed

the state's first university system, a railroad regulatory board, and a corrupt

practices law. Progressivism in Florida was tempered by the South's

conservatism and the state's lack of a strong urban, middle class population,

the key to Northern reformers.

Not all

reformers were the progressive kind. Colorful Reverend Sidney Catts mixed Populist

ideas with a strong anti-Catholic and anti-Negro campaign. He drove his Model-T

into Tallahassee

to become Governor despite the opposition of more powerful candidates and most

of the state's newspapers. Catt's plans for change were killed in part by the

outbreak of World War I.

The Florida

Jim Crow laws were just some of the many reasons why Florida lost talented African-Americans. Asa Philip Randolph of Crescent City

went to New York City and started the Pullman's Union. James Weldon Johnson of Jacksonville was one of

the founders of the NAACP.

The Florida

Jim Crow laws were just some of the many reasons why Florida lost talented African-Americans. Asa Philip Randolph of Crescent City

went to New York City and started the Pullman's Union. James Weldon Johnson of Jacksonville was one of

the founders of the NAACP.

In 1915, the State of Florida

started a state highway program. It became the absolute necessity to the later

development of Florida,

as important as the construction of the railroads in the 1880's. The leaders of

what would become the Florida

Land Boom were already

arriving before World War I.

Carl Fisher was developing the Dixie Highway Association to promote a motor route

from Chiacgo to Miami, a cavalcade first completed in 1915. J. F. Jaudon, another promoter, tried

to convince the state to connect Miami with Tampa. From 1910 to 1920,

promoters and developers were starting a building boom of suburbs in Florida's major cities.

They were meant for Floridians, but attracted a market of Northerners. There

was Telfair Stockton in Jacksonville, Walter

Fuller in St. Petersburg, and Al Swann and

Eugene Holtsinger in Tampa.

The Civil War had not ended the status of

the agrarian classes. Most rural African-Americans and poor whites found

sharecropping and tenant farming the only routes to survival in much of

Panhandle

The Civil War had not ended the status of

the agrarian classes. Most rural African-Americans and poor whites found

sharecropping and tenant farming the only routes to survival in much of

Panhandle

Towns like Palatka shifted from

agriculture to tourism. Everyone seemed to be riding the steamboats. Robert E.

Lee and

Towns like Palatka shifted from

agriculture to tourism. Everyone seemed to be riding the steamboats. Robert E.

Lee and

![]() Soon 200 sponge ships operated out of

Tarpon Springs and a vibrant community of Greek Orthodox settlers was added to

the waves of change in

Soon 200 sponge ships operated out of

Tarpon Springs and a vibrant community of Greek Orthodox settlers was added to

the waves of change in

The

The