FLORIDA

OF THE RAILROAD BARONS

POLITICAL CHANGE AND ECONOMIC GROWTH IN FLORIDA 1880-1900

THE POLITICS OF LAND

Just as the Louisiana Purchase opened the West to settlers in 1803, the Disston Purchase

of 1881 cleared the way for a mass development of South Florida, a

development that would seriously reshape Florida's

political and economic future.

Thirty

years earlier the State of Florida purchased

from the Federal Government's Swamp and Submerged Lands

program millions of acres of land for public sale and railroad construction.

The Florida

Internal Improvement Fund held title to this land, but during the Civil War era

its trustees found few customers except land speculators. Most payments were

made in worthless Confederate script, rendering the entire system about a

million dollars in debt and tied up in legal battles.

The

largest creditor of the state debt was

Francis Vose who tied up the land in court

until the state found the money to pay off its debts. The Bourbon Democrats,

mostly planters and businessmen, did not want to spend tax moneys on this debt,

but Florida

needed to clear the debt to expand. Investment in the least populated state

east of the Mississippi was stymied, but

Governor Bloxham found a white knight to rescue the

state in Philadelphia

saw manufacturer HAMILTON DISSTON .

River Landing At Jacksonville

River Landing At Jacksonville

Disston recognized

the tremendous potential of Florida real

estate south of Gainesville and agreed in 1881

to purchase four million acres of "listed swamp and submerged lands",

from the Kissimmee Basin to the Everglades, with large sections along

the Gulf Coast, at just twenty-five cents an

acre. Most of the land was suitable for some form of successful agriculture.

Tallahassee businessmen cheered their Northern savior

and the ending of debts without increased tax burden. Disston

was no generous patron; he realized the potential wealth of much of his

purchase. He was also no friend to the hundreds of farmers who tilled in the Kissimmee Valley under the Armed Occupation Act of

1842. The Swamp Act superseded their homestead titles and they only had to pray

Disston did not demand payment for their isolated

farms.

Disston's canal

company immediately dredged large sections of fertile muck lands out of the Kissimmee marshes.

Overnight new agricultural regions opened up.

In the Pinellas Peninsula,

Disston started a town on the bayou of Lake Butler,

invited rich Northern to build winter homes, and made the birth of Tarpon

Springs. Disston City, today near the town of

Gulfport, was opened in 1884 as the beginning of that region's farm growth.

The

intrusion of Disston's huge dredges in the Caloosahatchee Valley was a warning to the cattlemen

that the days of the homesteaders were beginning. In the winter of 1884-85

hundreds of Northern visitors arrived in the region including Thomas Alva Edison who decided to

bring a prefab winter complete, complete with South Florida's first swimming

pool, to Fort Myers. The father of the electric bulb and the phonograph

attracted dozens of other winter residents including Henry Ford.

Before the

railroad steamboats controlled the destiny of much of Florida. If you did not live along the coast

or along a navigable river, you were living in isolation. The fur trappers and

Seminoles, cowboys and fishermen ruled the frontier, but not for long.

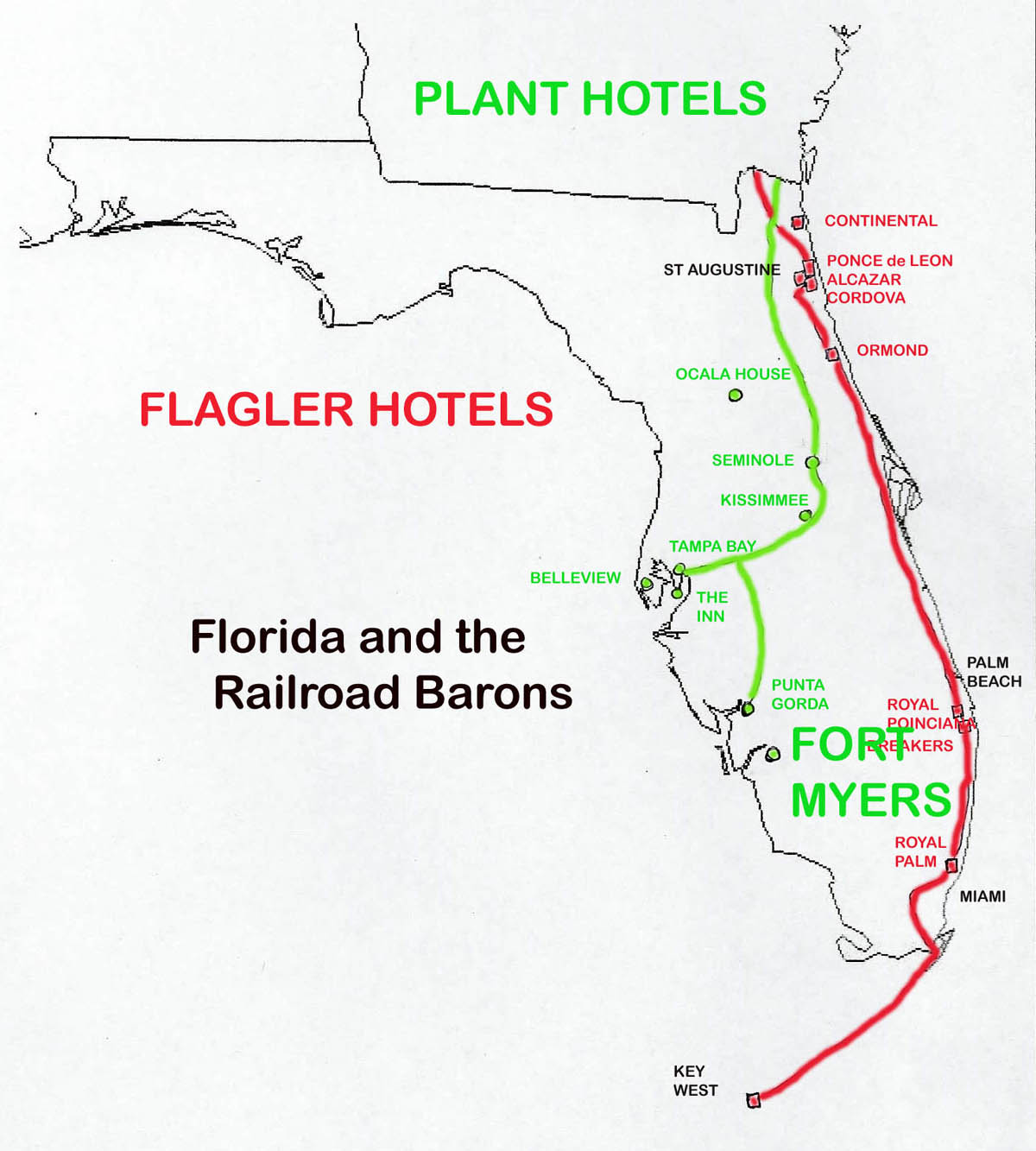

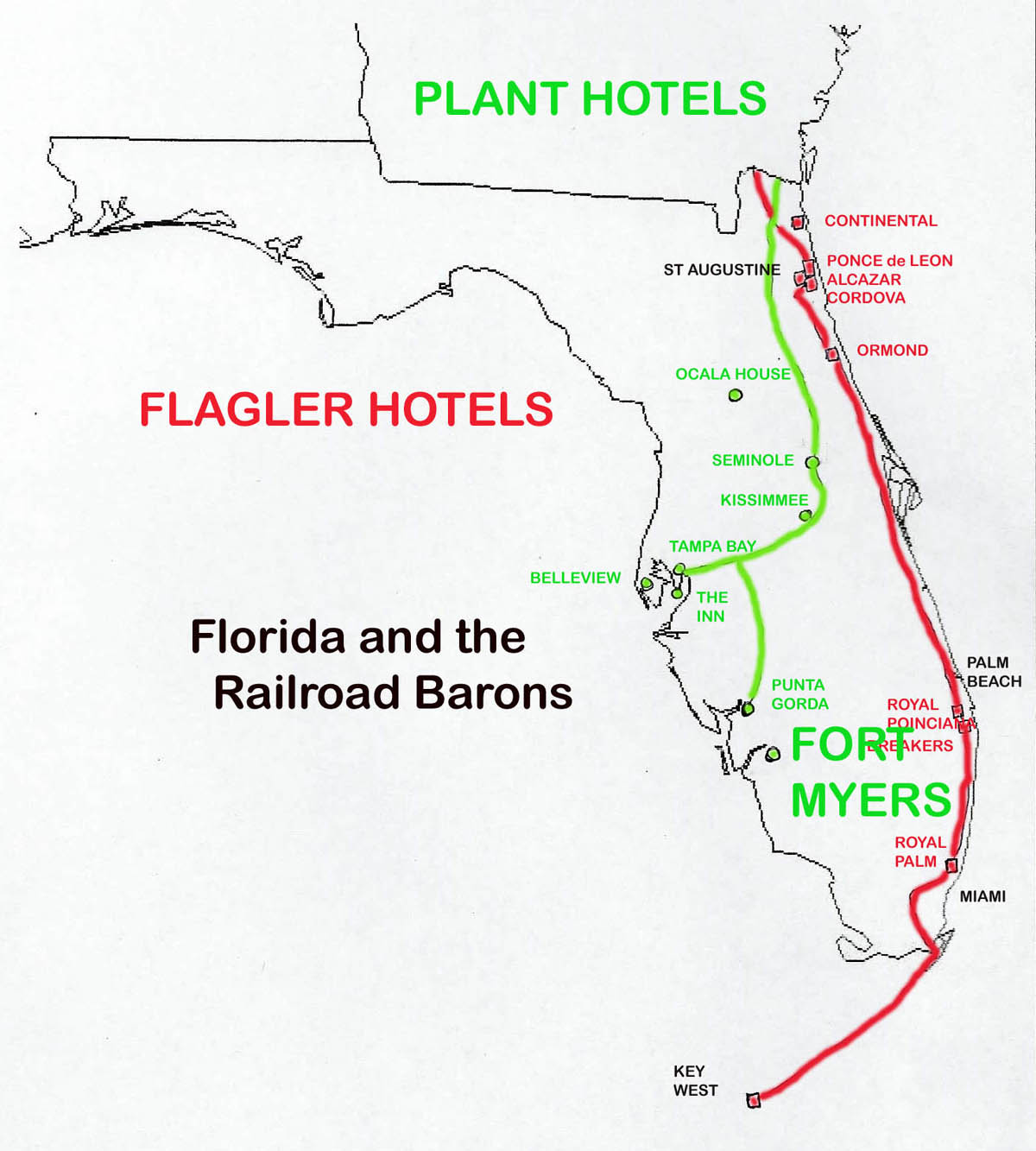

THE RAILROAD BARONS OF FLORIDA

The Disston Purchase stimulated the interest

in railroad builder, for the State of Florida could offer land deals to

railroad development much like the transcontinental railroad system growing in

the West.

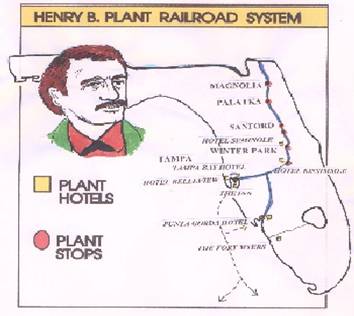

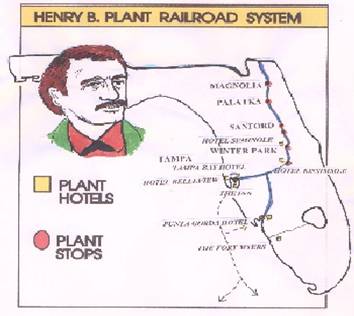

The

greatest development was due to three major railroad barons: William D. Chipley in the Panhandle; Henry B. Plant on the Gulf of Mexico;

and Henry F. Flagler on the

Atlantic Coast. Their domain contained more than just railroad track - they

built hotels, roads, and villages. Their track gave birth to new towns and

small trunk railroad developments.

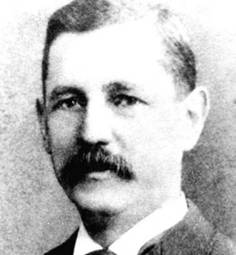

WILLIAM D. CHIPLEY, the son of a Georgia Baptist preacher,

became the most important developer of the growth of West Florida, an area of

lumbering and farming interests. Chipley had a knack of buying up bankrupted

railroads and turning them into profitable enterprises, by improving the

rolling stock and developing a shipping system that saved farmers money. In

1874, he received a charter to construct the Pensacola

and Atlantic Railroad across West Florida to Apalachicola.

The Panhandle was dependent upon river transportation which only flowed

southward until Chipley spanned the rivers and connected the Panhandle to

northbound railroads in East Florida.

Chipley's

railroad promoted large scale development of the Panhandle's lumber and farming

assets. It was, however, not until 1906 when developer George M. West started the Gulf Coast Development Company on St. Andrews Bay that coastal urban centers

developed. West named his fishing port Panama City since it was halfway between Chicago and Panama. The railroad turned the

steamboat towns into fishing villages.

THE WEST

COAST

Further down the West Coast, a Connecticut

businessman Henry

Bradley Plant started the railroad boom when he obtained a charter

for a South Florida Railroad from

Sanford on the St. Johns River to Tampa Bay.

Plant's railroad turned Tampa into a deep water

center for freighters and steamers from Cuba

and South America. The rail line opened up the

region to citrus and vegetable growers for it no longer took twenty days to

reach Northern markets by boat.

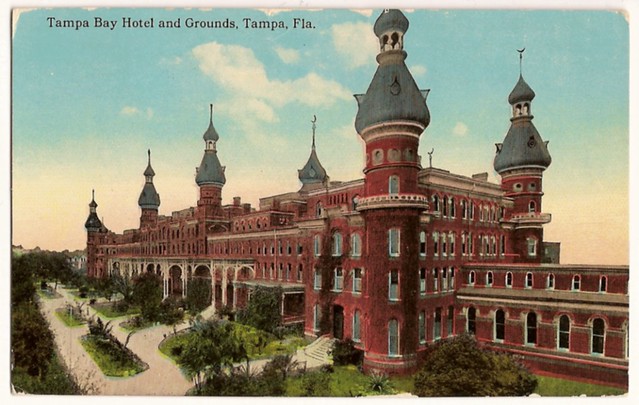

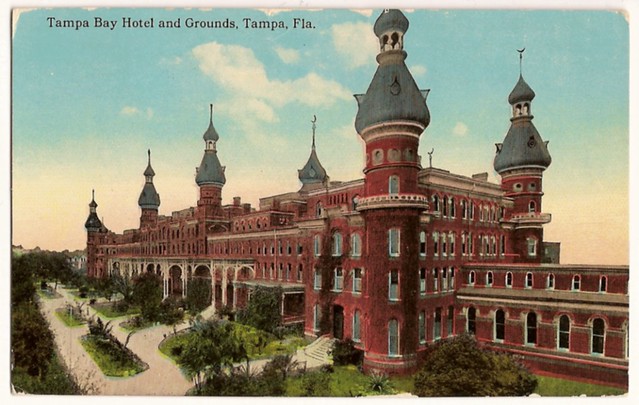

With two years Henry Plant's railroad had

attracted the Key West cigar industry and

Northern manufacturers to Tampa,

as well as a host of investors who started trolley lines and electric

companies. Nothing was as spectacular as Henry Plant's largest hotel, the Tampa Bay Hotel, on the Hillsborough River

in downtown Tampa.

At one hundred dollars per day, Plant hoped to attracted

the Northern rich to his empire. Plant's railroad ended Cedar Key's reign as a

passenger terminal.

With two years Henry Plant's railroad had

attracted the Key West cigar industry and

Northern manufacturers to Tampa,

as well as a host of investors who started trolley lines and electric

companies. Nothing was as spectacular as Henry Plant's largest hotel, the Tampa Bay Hotel, on the Hillsborough River

in downtown Tampa.

At one hundred dollars per day, Plant hoped to attracted

the Northern rich to his empire. Plant's railroad ended Cedar Key's reign as a

passenger terminal.

In 1885,

the Orange Belt Railroad of Sanford

was sold to an ambitious Russian refugee named Peter A. Demens. With a Disston grant, Demens built a

railroad down the Pinellas peninsula, fostering such towns as Dunedin,

Clearwater, and Largo. General John WIlliams,

pioneer of St. Petersburg and former Detroit Mayor, wanted the port town named

for his home city, but in a coin flip, the town was baned

for Demen's Russian home St. Petersburg. Demens dreamed of a

commercial port, but when the American Medical Society in 1885 named St. Petersburg "The Health City",

Demen's city became a retirement and resort

community.

THE ATLANTIC

COAST

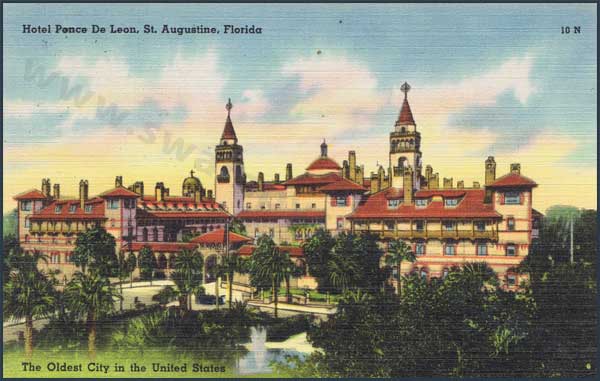

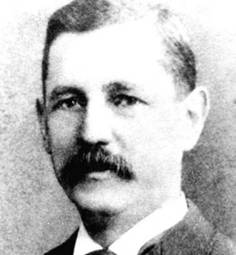

HENRY MORRISON FLAGLER was the most ambitious of the railroad

barons since his empire eventually stretched from Northeast Florida to Key West. The son of a

poor New York

minister, Flagler lived a Horatio Alger story by rising from country clerk to

bookkeeper and business partner of John D. Rockerfeller.

He came to Florida in 1879 due to the

deteriorating health of his first wife, and was recruited by Florida's business community to consider a

new career.

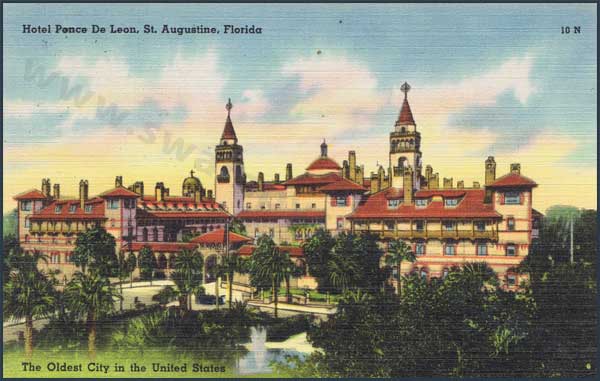

In 1885 he

purchased the small Jacksonville to St. Augustine

to Halifax Railroad and started thirty

hour Pullman service to New York City.

The idea immediately made St. Augustine a

winter destination to railroad tours. He built three hotels in St. Augustine, but the

death of his first wife and remarriage convinced him to continue southward.

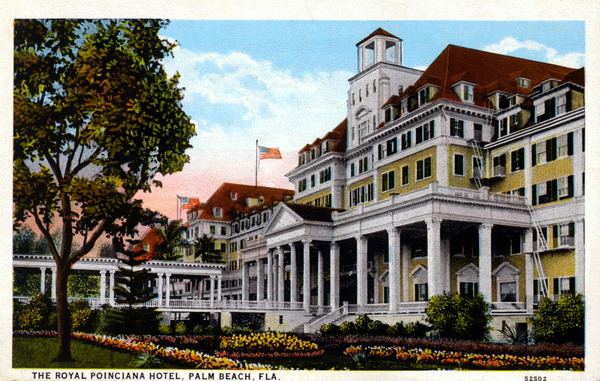

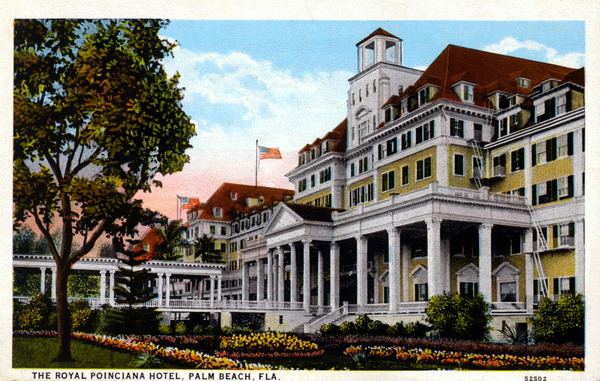

In 1893, he selected a small, sandy island

called Palm City and built a huge hotel called "The Breakers" to promote

his railroad growth. When the railroad reached Palm Beach,

affluent Northerners were already planning their winter mansions. Flagler built

his new wife a massive marble winter mansion called Whitehall and Palm Beach soon became the winter watering hole of America's

industrial elite. Flagler topped even this with the 1,500 room Royal Poinciana Hotel, the largest

wooden hotel in the world. Now, Henry Plant's Biltmore in Pinellas County

is the largest.

In 1893, he selected a small, sandy island

called Palm City and built a huge hotel called "The Breakers" to promote

his railroad growth. When the railroad reached Palm Beach,

affluent Northerners were already planning their winter mansions. Flagler built

his new wife a massive marble winter mansion called Whitehall and Palm Beach soon became the winter watering hole of America's

industrial elite. Flagler topped even this with the 1,500 room Royal Poinciana Hotel, the largest

wooden hotel in the world. Now, Henry Plant's Biltmore in Pinellas County

is the largest.

Flagler

originally planned to retire in Palm Beach, but the freeze of 1894-95 convinced

him that lands further south than Indian River would one day yield America's

winter crops. Near old Fort Dallas on the Miami River

lived Mrs

Julia D. Tuttle who sent Flagler a blossoming orange branch in the midst

of the freeze. With Plant extending his domain down the Gulf

Coast, Flagler took the challenge to

continue his railroad to Biscayne Bay.

Hundreds

of settlers sailed ahead to Lemon City, the only developed port in Biscayne

Bay. In 1896, when Flagler's train reached the Miami area, some 3,000 new residents were

waiting. Miami did not attractive the elite of Palm Beach, but began to grow as

a tourist center. Flagler wanted to control the Miami waterfront,

but found the pioneers wanted a bay front park.

In 1912

Flagler was still following his dream when he gained funding for one of the

great engineering feats in American history - the construction of a railroad to

the island of Key West. Ninety-one miles of road and

thirty-eight bridges allowed Flagler's trains to reach Key West. Unfortunately, the Hurricane of

1935 would destroy Flagler's amazing Overseas

Railroad.

RAILROADS AND INDUSTRY IN GILDED ERA FLORIDA

The railroads were necessary in the rapid transportation of bulk goods

and agricultural products that had to reach Northern markets in a few days

after harvesting. The railroad network bolstered an old Florida industry: the sugar industry. Hamilton Disston himself

started the successful Florida Sugar Manufacturing Company in the Clewiston area.

Flagler's railroad allowed for sugar production along Lake

Okeechobee.

A more

unusual development was popularized by one Albertus Vogt, who became famous when his African-American helper tied his

fishing boat to the remains of a fossilized bone and Vogt realized that Florida

was rich in high grade phosphate in both the upper Peace River Valley and

around Dunnellon.

Vogt became known as the "Duke of Dunnellon", a

millionaire when his fields were active and broke when he his investment went

dry. He owned thousands of acres and promoted at least four phosphate booms.

Once when low on cash, but high on land, he even buried leaking oil cans on his

property to sell the useless land to speculators. Phosphate mining provided a

reliable product for shipment by railroad or boat along the Gulf Coast.

Vogt became known as the "Duke of Dunnellon", a

millionaire when his fields were active and broke when he his investment went

dry. He owned thousands of acres and promoted at least four phosphate booms.

Once when low on cash, but high on land, he even buried leaking oil cans on his

property to sell the useless land to speculators. Phosphate mining provided a

reliable product for shipment by railroad or boat along the Gulf Coast.

At a time when young African Americans were leaving the Deep South in record

numbers to seek opportunity in the factories of Northern cities, the growth of

railroads and other industries in Florida were attracting African Americans

from Panhandle Florida, Georgia, and Alabama into Southern

Florida. A majority of the phosphate miners were black. Most of

the laborers on the large hotels were black. It was necessary to establish

residential communities for all the African Americans who serviced the growing

number of resorts and projects. New urban black villages grew up along the Florida East Coast.

AGRICULTURAL BOOM

The belief that Florida

land was too sandy or marshy for profitable development had been a common

concern in the Deep South for generations. The Florida

railroaders showed the entire world the bountiful crops that South

Florida could produce. Since South Florida land sold for a

fraction of Northern land and less than most farm land in the Deep South, the

homesteaders flooded down the rail lines into Florida in the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries.

People

across the farm belts of the United

States were heard sprouting the railroad

promotion slogans, "Below the frost line" and "ten acres and

independence". At the turn of the century one thousand dollars gave you a

nice piece of Florida

acreage and a cottage. Such an investment could yield $3,400 in tomatoes in one

year. Despite the need for huge doses of fertilizer and heavy labor, Southern

farmers considered Florida

an agricultural paradise.

The cattle kingdom would never be the land

of open range and long trail drives, but the development of scientific cattle

breeding had arrived by 1900. Prior to experimentation, ninety per cent of Florida's herds were

ill-fed, unattended beef herds. The resultant beef products were mainly for

local consumption. Natal hay from South Africa and the introduction

of foreign livestock like the Indian Brahman began to change the cattle

industry.

OVERVIEW

In 1876 Florida was a backward

agricultural state with poor transportation connections to the North and Midwest. By 1900, the foundation of the state's growth had

been forecast with the construction of railroad systems along both coasts into Southern Florida. The railroad baron had started the

winter hotel resort industry at a scale that the early steamboat companies

along the St. Johns River could not imagine.

Despite these changes, the mind and spirit of Florida society was not ready for too many

changes.

With two years Henry Plant's railroad had

attracted the

With two years Henry Plant's railroad had

attracted the