CIGAR

MAKING IN

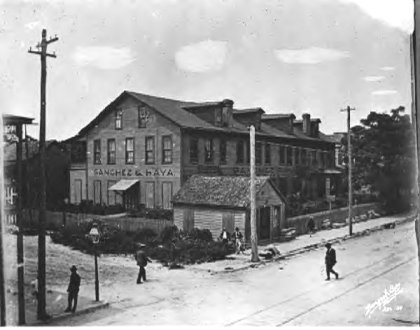

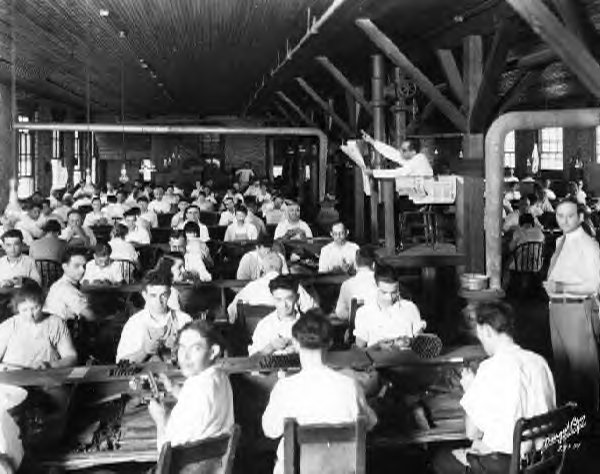

The cigar industry that developed in

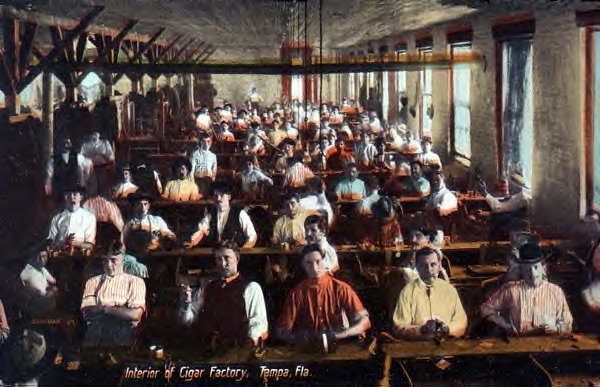

![]() The skilled cigarmakers, mostly

Spanish, were well paid, based upon their skills and speed. They often were in

charge of the all important apprenticeship system training new artisans.

The skilled cigarmakers, mostly

Spanish, were well paid, based upon their skills and speed. They often were in

charge of the all important apprenticeship system training new artisans.

Cigarmakers were paid $28.00 per 1,000 for the top perfecto

brand cigars while the inexpensive cherutos

cigars often commanded a price of just $8.00 per thousand in 1910. Custom

jobs were only done by top artisans since the reputation of the brand was

impacted by these famous customers.

The skilled cigarmakers had a great deal of economic

and social power until the 1930's, for they could always be recruited by other

firms. They selected their own hours and often left the factories to dine on

The top cigarmakers' wives were

rarely in the work place. This was in part the traditional role of the wife in

Management and ownership of

Spanish

workers also dominated the positions of resagadores

(wrapper selectors) and escogedores (packers),

who played the key role of quality control of distribution and value. Each

year's tobacco crop was not uniform nor was the tobacco harvest consistent.

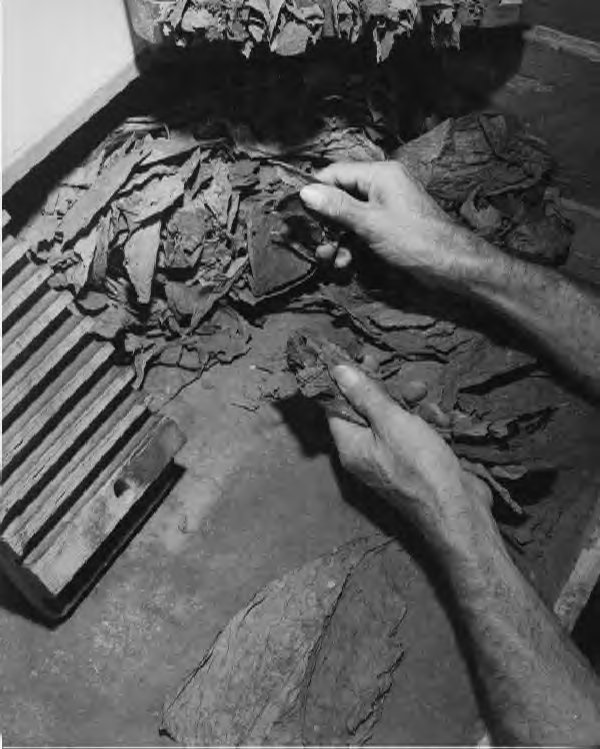

Spanish

workers also dominated the positions of resagadores

(wrapper selectors) and escogedores (packers),

who played the key role of quality control of distribution and value. Each

year's tobacco crop was not uniform nor was the tobacco harvest consistent.

The

Spanish controlled the job of chavatero (knife

sharpener) and any position in charge of the maintenance of factory equipment.

The

Spanish controlled the job of chavatero (knife

sharpener) and any position in charge of the maintenance of factory equipment.

Cubans rolled most of the

cheaper cigars, often from leftover tobacco or lower quality tobacco. Cubans

did rise to higher positions and many opened smaller shops, but the ethnic

stratification of many factories was against such promotions.

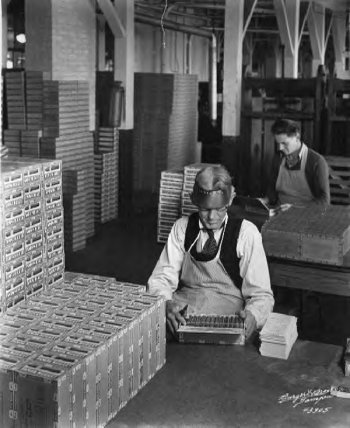

![]() By 1900 more and more women entered the cigar

industry, mostly in the positions at the stripping tables, later in boxing the

cigars. As second and third generation male Hispanics left the cigarmaking industry, women became an important labor

source.

By 1900 more and more women entered the cigar

industry, mostly in the positions at the stripping tables, later in boxing the

cigars. As second and third generation male Hispanics left the cigarmaking industry, women became an important labor

source.

The

development of mechanized, more inexpensive cigars clearly opened job

opportunities for women. Skilled artisans would not accept such positions even

in a poor economy.

The

development of mechanized, more inexpensive cigars clearly opened job

opportunities for women. Skilled artisans would not accept such positions even

in a poor economy.

Italians entered the cigarmaking industry at the

lowest ladder, often working in small factories. Salaries in such jobs were

insufficient for most and they found jobs in retail commerce.

Afro-Cubans, Italians, women, and African-Americans

handled most of the jobs that did not relate to the manufacturing of cigars.

The building maintenance jobs, the transportation and shipping jobs, and

general labor jobs were usually held by Afro-Cubans, Italians, and

African-Americans.

Transportation of construction materials between downtown and

One of the great symbolic sources of conflict between the

workers and management throughtout

Lectors were hired and paid by the workers,

who treasured the right to select the reading materials. Prior to 1898 the

concern by management included the issue of Cuban independence; after 1900, the

issue was the anti-management, pro-proletarian themes of the literature.

Socialist, anarchist, and communist literature mixed with local news and

popular novels like Emile Zola and Miguel de Cervantes.

Lectors were hired and paid by the workers,

who treasured the right to select the reading materials. Prior to 1898 the

concern by management included the issue of Cuban independence; after 1900, the

issue was the anti-management, pro-proletarian themes of the literature.

Socialist, anarchist, and communist literature mixed with local news and

popular novels like Emile Zola and Miguel de Cervantes.

Since the workers selected the publications and novels, the lector was a voice

piece for the workers. Talented lectors commanded great salaries as well as great

resentment by the manufacturers.

The decline of the lector was signalled as a decline

of the workers' movement and their continual struggle against the manufactuers. Unfortunately, forces beyond the control of

both the skilled cigarmakers and the manufacturers

would forever change the cigarmaking industry and end

an entire