AFRO-CUBANS

IN TAMPA

On April 12, 1886, when the first Cuban

cigar-workers arrived in

While emancipation for Cubaís one-third

Afro-Cuban population was not achieved until 1886, some twenty years after

slavery ended in the United States, free Afro-Cubans existed under Spanish rule

in a more subdued and flexible racism than in Florida. In

Race relations in

Cigar workers, both black and white, included

many revolutionary leaders. The establishment of a cigar industry in

Many cigar owners, such as Vicente Martinez Ybor were sympathetic to Cuban independence and fair

treatment of Afro-Cubans. He was less supportive of trade unionism. Still, Ybor allowed Cubans to collect funds for their

revolutionary cause in his facilities.

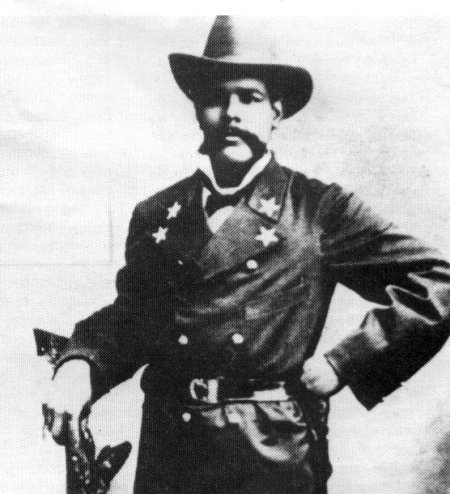

Racial divisions and lack of unified

leadership undermined these efforts until the rise of prominence of the great

Cuban writer JOSE MARTI, who

first visited

After an attempted assassination, Marti

always stayed at the Pedroso Boarding House at

![]() While many

Afro-Cubans returned to

While many

Afro-Cubans returned to

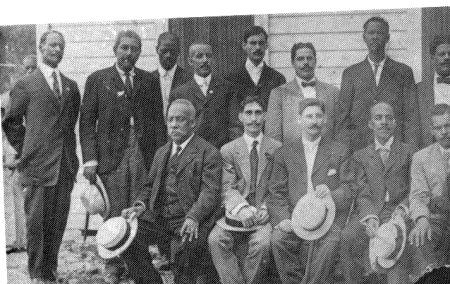

On October 26, 1900, the MARTI-MACEO SOCIETY

was started in the home of Ruperto and Paulina Pedroso. At first educational and recreational were

started, with medical assistance added in 1904 when the Marti-Maceo merged with LA

UNION, a West Tampa group started by Juan Franco. In 1908 LA UNION MARTI-MACEO became

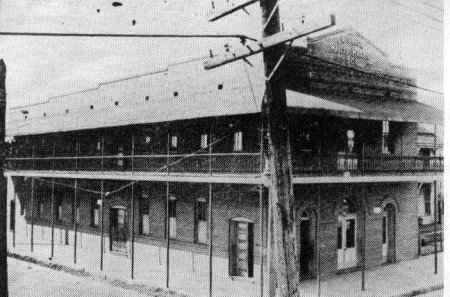

incorporated and started a brick clubhouse at

With 300 members, La Union Marti-Maceo could provide social and educational services

unavailable in segregated

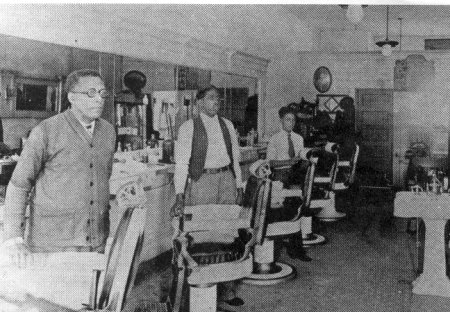

Ninety percent of the male Afro-Cubans worked

as cigar-workers, while another 15% of the female Afro-Cuban population worked

in cigar factories, most as tobacco leaf strippers. The cigar industry was

expanding and mobile, with salaries based upon skill, not race. Yet, even the Cigarmakers International Union was openly segregationist

and racist in policies favoring white workers. Black cigar-workers had little

choice but to remain in the union so the Club was their refuge from multiple

discriminations.

The Club remained financially stable until

the 1930�s from sales from the cantina and food, and by renting their

dancehall to other groups. At least 25% of all Afro-Cuban households had single

male relatives as tenants and many of these mobile men made the Club a

restaurant and social center.

![]()

The quick decline of the cigar industry in

the Great Depression which followed the damaging destruction of the union in

the strike of 1931, was particularly damaging to

second generation Afro-Cubans. Job opportunities seemed better in

The New Deal helped Afro-Cubans and African

Americans know each other better. The Club was used as a federally-sponsored

music academy. The dancehall hosted concerts by Fats Domino, B. B. King, and

Cab Callaway.

In

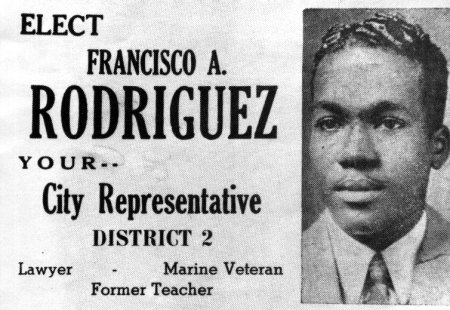

The Civil Rights Movement in the late 1950�s

had the full support of Afro-Cubans, with lawyer Francisco Rodriguez, a leader

with the NAACP, and educator Aurelio Fernandez, as key organizers. The start of

integration in 1962-1964 began at the

In the 1960�s urban renewal resulted

in the destruction of the deteriorating Union Marti-Maceo

clubhouse. A smaller structure was built at