FLORIDA

OF THE SEMINOLES

THE STRUGGLE FOR THE SOUTHERN FRONTIER

THE SEMINOLE WARS OF FLORIDA

No event

hindered the development of the Territory

of Florida and slowed the

effort of Floridians to gain statehood more than the Seminole Wars. The conflict between white man and Indian in Florida became the longest continuous war in which the United States

Government engaged an enemy. To the Seminole, it is a war that never officially

ended.

The origin

of the Seminole conflict date back to Governor Moore's invasion into Spanish Florida in 1704 in which

he introduced bands of Creeks into the region to destroy the Spanish Apalachee. Many of these Indians remained in Florida and later joined the British to fight Georgia

settlers during the American Revolution.

The

development of the Southern states disrupted the boundaries of all native American groups in the region. In the mid-1700's

Creeks, predominately of the Hitchiti-speaking Oconee tribe, left Western Georgia

and moved southward to the Gainesville

prairies. Perhaps they were adventurous young Indians since Seminole means "runaway" or

"wild". More likely they were groups of Indians who found Spanish Florida a save refuge

from the onslaught of white settlements.

While

these Seminoles were not direct participants in the Creek Wars of 1813, their ability to adapt to such European ways

as wheat farming and cattle raising aroused the anger

of Georgia

farmers who accused them of stealing their cattle. Most of the Seminole herds

appeared to be wild Spanish stock. More significantly, planters noted that the

Indians welcomed and accepted the arrival of runaway African-American slaves.

When Florida became a Territory in 1821, its first Governor Andy Jackson considered the

some 7,000 Seminoles in Florida a major

handicap in the development of Florida.

Busy with the settlement of Americans, Jackson

did not have the time and manpower to curtail the arrival of even more Creeks

along the Panhandle.

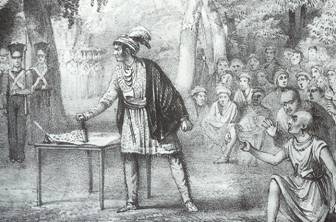

THE TREATY OF MOULTRIE CREEK

In

September of 1823, the next Territorial Governor William F. Duval met the Seminoles at Moultrie Creek on the St. Johns River.

Duval proposed the creation of a reservation area in the southern interior of

the peninsula of Florida as the solution for the two

peoples. After much contriving, most chiefs accepted the plan, provided the

West Florida Creeks were given a treaty for land along the Apalachicola River.

The Seminoles made no commitment on slavery or alleged stolen cattle, two

important issues..

The more

militant braves never complied with the

Treaty of Moultrie Creek. They had already been forced from their

traditional hunting grounds, changed their livelihood from farming to cattle,

and disliked any form of confinement. Neamathia, a

Mikasukis from North Florida, challenged

Duval:

"Do you think . . . I am like a bat, that hangs by

its claws in a dark cave,, and that I can see nothing of what is going on

around me? Ever since I was a small boy I have seen the white people steadily

encroaching upon the Indians, and driving them from their homes and hunting

grounds . . . I will tell you plainly if I had the power, I would tonight cut

the throat of every white man in Florida.

Neamathia's fears

were quickly realized as conflict between Indian and white settler started

almost immediately after the signing of the document. By 1828, the Florida Legislative Council was urging Congress to remove

all Seminoles from Florida

Territory. Northern

Congressmen were reluctant to bring up the issue of the Smeinoles

in committee, but the new President Andrew Jackson, not friend to the Indians,

was firm in his plans to remove all troublesome tribes west of the Mississippi River. Since Florida

was a much needed slave territory, Southern Congressmen vigorously backed Jackson's plans.

Upon the

threat of losing their annual Government annuity to pay the cost of moving into

the new reservation area, the old chiefs agreed to discuss the problem with

Indian agent Colonel James Gadsden.

In the so-named Treaty of Payne's

Landing, outside Silver Springs, the chiefs agreed to send six Seminole

inspectors to Oklahoma

to check the proposed Seminole tribal grounds.

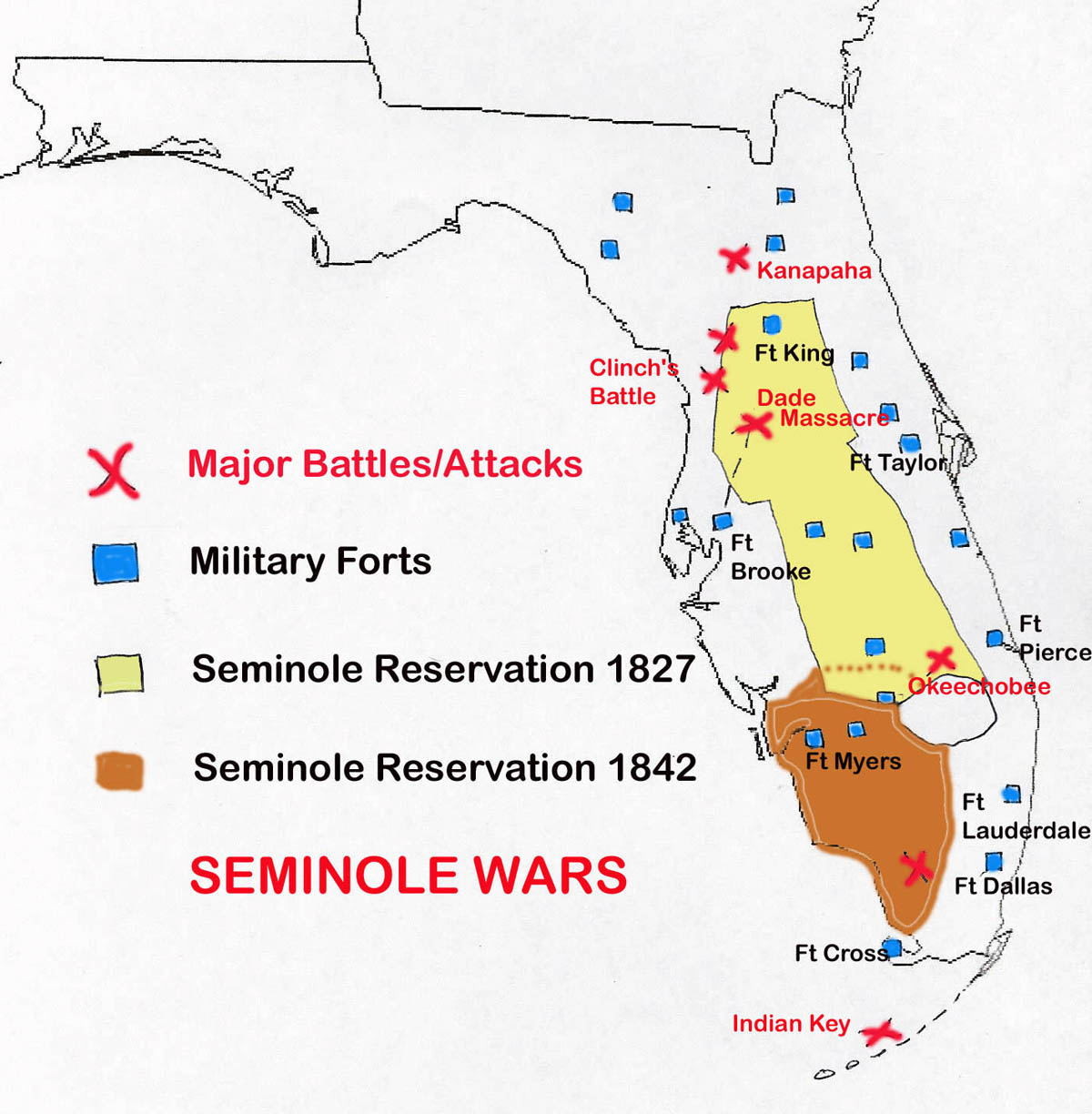

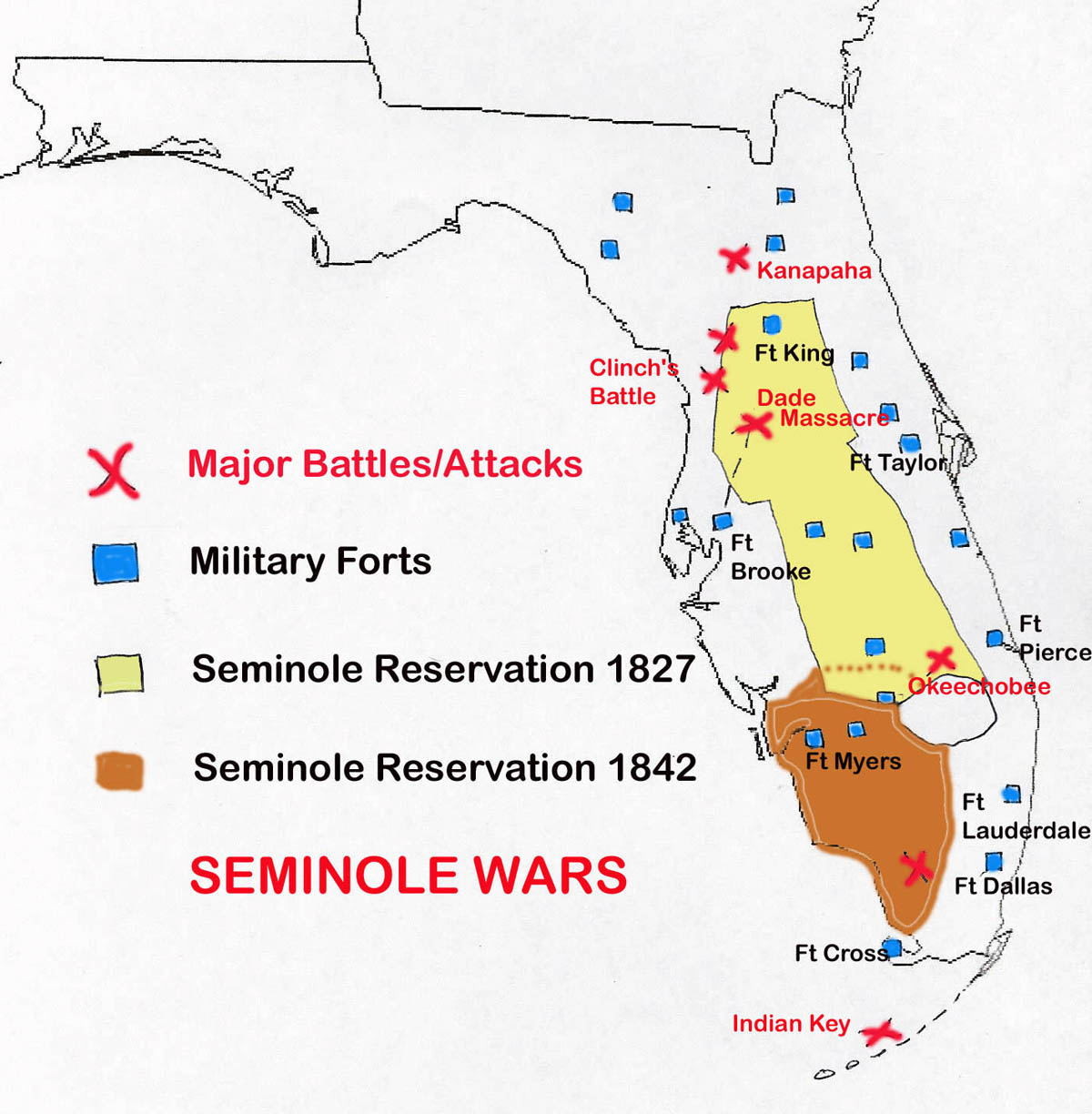

THE SECOND SEMINOLE WAR

The

inspectors would sign the Treaty of Fort Gibson

(Oklahoma) after their visit to Oklahoma. It is doubtful

if the Seminoles fully understood the full extent of the treaty, thanks it is

believed to the bribing of interpreters by Government agents. The Seminoles

were given a tourist tour of only the most desirable areas of the reservation.

They were not told they would share their reservation with other tribes not did

they satisfaction to their concerns about the suitability of the land to

Seminole crops.

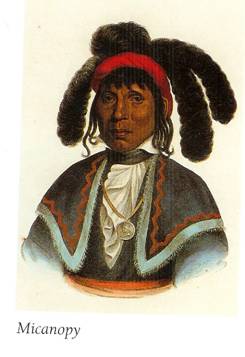

The older

chiefs led by Micanopy accepted

the Treaty of Fort

Gibson, but younger

Indians became infuriated when details of the agreement became interpreted. A

young Indian named Osceola,

recently arrived from the Panhandle and vowed to

organize the younger Indians against the plan. Although wed to a Seminole, Osceola's mother was Choctaw and his father was believed to be a white trader from Mobile. Tribal websites note this fact today. Osceola knew white society and he knew that the treaty did not even guarantee that the Seminoles would not have to share land with other tribes.

Osceola

was particularly incensed when he discovered the Treaty indicated that runaway

slaves who lived with the Seminoles, many of them intermarried into the

villages, would remain in Florida.

It was apparent to Osceola, they would be returned to slavery even if it were

impossible to locate their previous owners.

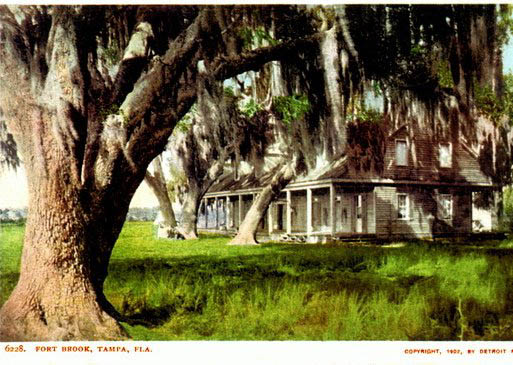

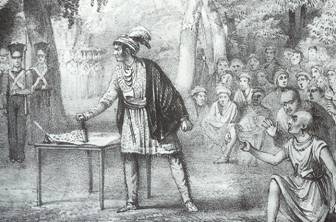

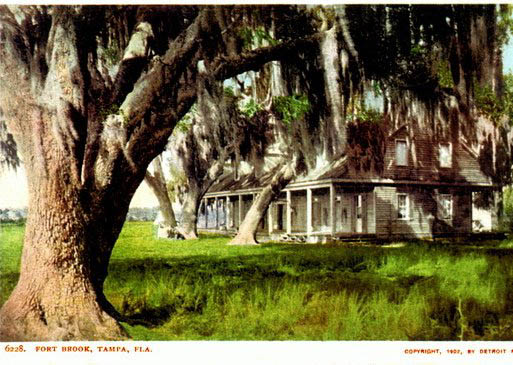

While the

older chiefs prepared for travel to

Fort Brooke (Tampa) established for the debarkation by boat to Oklahoma

via the Mississippi-Arkansas River systems, Oscola

quickly thrust his knife into a copy of the treaty, shouting:

" Am I a Negro slave? My skin is dark, but not black! I am an Indian, a

Seminole. The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red

with blood, and then blacken him in the sun and rain, where the wolf shall gnaw

his bones and the buzzard shall live on his flesh."

In December

of 1835 Osceola began his war in dramatic fashion when his men ambushed the new

Indian agent General Wiley Thompson,

by his office just outside the gates of Fort King

(Ocala). The

Seminoles next killed Chief Emathia, who was helping Thompson recruit Indians to

go to Fort Brooke

(Tampa). The

reaction by the United States

Government was to send reinforcements even though there were few trained foot

soldiers in Florida.

An even

more stunning event would soon follow - the worst defeat of U.S. troops to the American Indian

outside of the stupidity of George Armstrong Custer. Major Francis L. Dade and 110 soldiers, many of them untrained artillery

soldiers, was ordered from Fort

Brooke (Tampa)

to bolster forces at Fort King (Ocala).

Halfway to their destination they were ambushed by a large band of Seminoles

and their slave allies, at a site where many of the Indians hide in the

unlikely spot of a lake bank. Only a few soldiers escaped the attack.

Unfortunately

for the Seminoles, the Dade Massacre

pressured Northerners in Congress to accept Southern proposals for more troops

and equipment. Since the Florida militia could

not assure protection to farmers and planters, homesteaders south of Gainesville fled to the

safety of the coast. The Government decided the Seminoles had to be surrounded

by a ring of small wooden forts where U.S. troops could operate in

protecting a region.

Fort

Lauderdale, Fort Myers, Fort Meade, and Fort

Pierce were started as forts in the Seminole Wars.

Even Fort Brooke

on Tampa Bay

was subject to increased protection as many Seminoles slipped away just minutes

for scheduled departure to Oklahoma.

Eventually, Seminoles were keep on Egmont Key to

assure their safe removal.

Federal

troops adopted a strategy of crisscrossing the interior by boat and foot

driving the Seminoles into open country. The major weakness of the Seminoles

was their women and children could not move around like the warrior units so the U. S. Government adopted a policy

of hunting down, uprooting, and capturing the Indian villages.

The Capture of Osceola A Prison Cell in Saint Augustine

In 1837

Osceola was captured under a flag of truce and delivered to General Thomas Jesup,

a Southerner in charge of the Indian war strategy. Osceola refused to accept

any Oklahoma agreement so he was transported to Four Moultrie's prison outside

Charleston, South Carolina, where the great Seminole warrior died of throat

inflammation. Even in death, Osceola was attacked as soldiers beheaded his body

before burial.

SEMINOLE WAR IN THE SWAMPS

The

surviving Seminoles were driven southward toward the Everglades.

They were used to adjusting their way of life, even some of their cultural

activities just to survive. Some Seminoles had married the last remaining Calusa and adopted an economy of hunting and fishing in the

swamps.

FORCED MOVEMENT OF SEMINOLES SOUTHWARD IN FLORIDA

FORCED MOVEMENT OF SEMINOLES SOUTHWARD IN FLORIDA

Federal

troops built Fort Dallas on the banks of the Miami River to block the

route into the Everglades on the east and constructed Fort Dulaney at the mouth of the

Caloosahatchee to supply Fort Myers and Fort Denaud up the river. At the

latter fort Captain B. L. E. Bonneville launched boat patrols to disrupt the

Seminoles.

In May of

1838 General Alex Macomb signed

the Biscayne Bay agreements with Chief Chitto-Tustenuggee

of the Muskogees and Miccosukee. This temporary

provision allowed the Indians to stay in a district, from Punta Rassa at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee to Lake

Okeechobee, then south to the Shark

River and the Gulf. The

Indians considered this the first step to staying in Florida, but even this marshy wilderness

could not protect the Indians. Farmers and trappers ignored the agreement, and

Cuban fishermen, long time trading friends to the Indians, were told to avoid

Indian contact.

In July of

1839, open warfare broke out in Southwest Florida

when traders and Indians clashed. Chekiki, the last of the Calusa

tribe, allied his people with the Seminoles in a last ditch attempt at freedom.

THE THIRD SEMINOLE WAR

In 1841,

when North Florida was booming with settlers, South

Florida was still a war zone. Congress appropriated more than one

million dollars to capture by bribe or bullet the surviving Indians. The Indian

Council, headed by Holatta-Micco

(Billy Bowlegs) was determined to defend the Biscayne holdings. The

Third Artillery under Major Childs and

Lt. John McLaughlin began to crisscross the swamps with the intent of

destroying anything that would help the Seminoles. By 1842 230 Indians had been

captured by this strategy.

Billy Bowlegs of the Third Seminole War Andrew Jackson

There was

great pressure in Congress among Northerners to curtail this expensive and

bloody conflict, which could only result in the creation of another slave

state. A truce was started when Billy Bowlegs agreed to stop hostilities. It

did not last.

Inspired

by the discovery of the rich muck lands of the Okeechobee area, Governor Thomas Brown encouraged cattlemen and

farmers, protected by the Florida

militia, to enter the region. Fort

Myers was developed into a full sized village. In

December of 1855, Lt. George Hardstuff, on a "survey" of Seminole

facilities, ram survey lines across Billy Bowlegs

prize banana garden. The Indians returned to the war.

Five

hundred dollar rewards for braves, $250 for women, and $100 for children were

offered to white bounty hunters. Indians could receive the same rewards for

giving up. The Seminoles rejected the financial rewards and began their guerrilla warfare. A band of forty Oklahoma Seminole could

not convince the Indians to surrender.

Billy

Bowlegs rejected bribes of $5,000 plus $100 per surrendered Indian, but when

his granddaughter was seized, he was forced to surrender. On May 4, 1858, the

last of the famous Seminole warriors met the soldiers at Billy's Creek and was

sent forever from Florida.

A handful of Seminoles remained in the Everglades,

but fighting ended.

The

Seminoles had delayed Florida

statehood for thirty years. They had never surrendered, each person allowed to

decide whether to accept a treaty. Now the frontier was ready for settlement

and only the Civil War would delay the potential growth of this last frontier.

![]()

FORCED MOVEMENT OF SEMINOLES SOUTHWARD IN

FORCED MOVEMENT OF SEMINOLES SOUTHWARD IN